The democracy in ancient Athens is still admired today. The institution of ostracism can be paradoxical, since no one was punished for a crime, but it was a political idea to maintain democracy and not to give a tyrant the chance to come to power.

So when in the old Athenian democracy a citizen gained great political power and became dangerous for the functioning of the state itself, there was the penalty of ostracism which meant 10 years of exile.

From 488 B.C., the Athenians gathered in the assembly church of the city district and took the shells with them, on which they wrote the name of the person they wanted to send into exile.

To be exiled, your name should be written on 6,000 or more shells. Plutarch, on the other hand, explains that there had to be at least 6,000 shells for the vote to be effective, and whoever had the most was exiled.

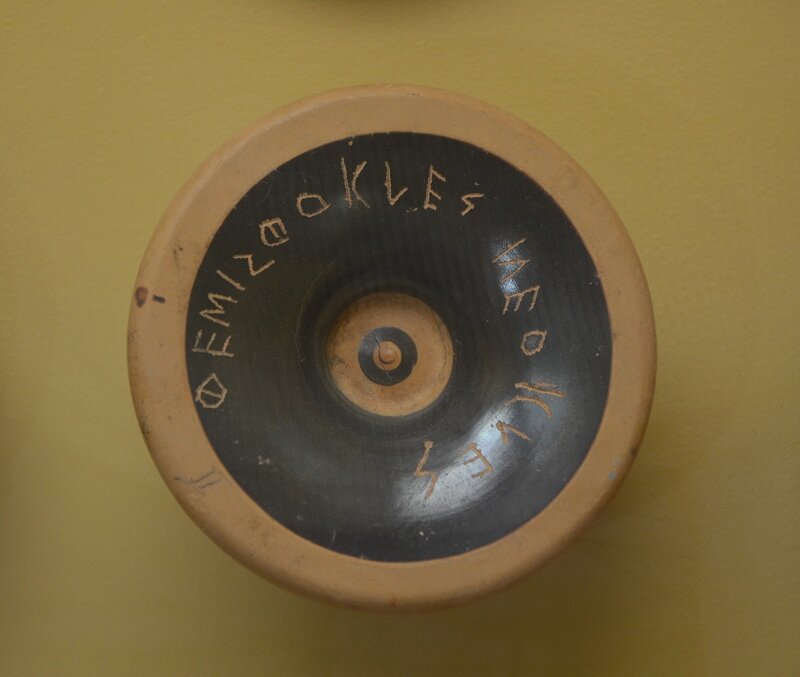

A set of ostraka bearing the name Themistokles, son of Neokles, part of a large series found in a well on the northern slope of the Acropolis. (Agora Museum, Athens)

The exile had to leave the city for ten years, but his property remained intact and he did not lose his political rights. So he could not influence the state or the political organ. Some of the politicians living in exile were Kimon, Aristides and Themistocles.

Of course, in any state and at any time in history, someone finds a way to exploit the law. So after a few years, every faction used the institution of ostracism to lead political opponents out of the city.

This brought the end of the institution, when Alcibiades allied with Nikias, so that their followers banished Ypervolos into exile.

An ostrakon inscribed with the name of Perikles (son of Xanthippos), the leading politician of mid-5th century BC Athens, responsible for the Classical redesign of the Acropolis.

Many returned earlier than ten years, while some others were asked to return in times of need. The institution lasted for a whole century, although the concept of ostracism changed over time.

The list of known ostracisms runs as follows:

487 Hipparchos son of Charmos, a relative of the tyrant Peisistratos

486 Megacles son of Hippocrates; Cleisthenes' nephew (possibly ostracised twice)

485 Kallixenos nephew of Cleisthenes and head of the Alcmaeonids at the time (not known for certain)

484 Xanthippus son of Ariphron; Pericles' father

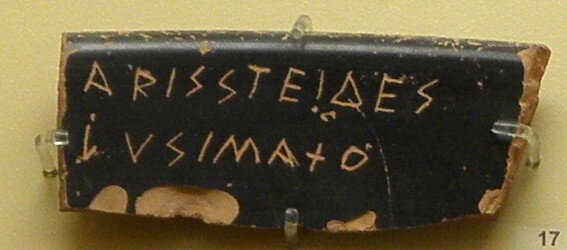

482 Aristides son of Lysimachus

471 Themistocles son of Neocles (last possible year)

461 Cimon son of Miltiades

460 Alcibiades son of Kleinias (possibly ostracised twice)

457 Menon son of Meneclides [less certain]

442 Thucydides son of Melesias

440s Callias son of Didymos [less certain]

440s Damon son of Damonides [less certain]

416 Hyperbolus son of Antiphanes (±1 year)

Around 12,000 political ostraka have been excavated in the Athenian agora and in the Kerameikos.The second victim, Cleisthenes' nephew Megacles, is named by 4647 of these, but for a second undated ostracism not listed above. The known ostracisms seem to fall into three distinct phases: the 480s BC, mid-century 461–443 BC and finally the years 417–415: this matches fairly well with the clustering of known expulsions, although Themistocles before 471 may count as an exception. This suggests that ostracism fell in and out of fashion.