As the pinnacle of antiquity’s ability in engineering, architecture and artistic beauty, the seven wonders of the ancient world still cast their shadow over human endeavour today. Jonny Wilkes explores each in turn for BBC History Revealed, from their construction to their ultimate fate.

Individually, the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World can be regarded as astounding architectural achievements or marvels of human imagination and engineering – but together, they form an ancient travel guide, there to challenge the limitations of the time and, literally, reach for the skies.

What are the seven wonders of the world?

They consist of a pyramid, a mausoleum, a temple, two statues, a lighthouse and a near-mythical garden – the Great Pyramid of Giza, Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Temple of Artemis, the Statue of Zeus, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Lighthouse of Alexandria and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Despite only being a short-lived collection – the last to be completed, the Colossus of Rhodes, stood for less than 60 years – and one of them, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, possibly not existing at all, the Wonders continue to capture imaginations and drive archaeologists and treasure hunters. They laid the foundations for what humans could achieve. Yet for all their fame, there are many questions surrounding these classical creations. Who decided what constituted a ‘Wonder’ in the first place?

As Greek travellers explored the conquests of other civilisations, such as the Egyptians, Persians and Babylonians, they compiled early guidebooks of the most remarkable things to see, meant as recommendations for future tourists – which is why the Seven Wonders are all around the Mediterranean Rim. They called the landmarks that bewildered and inspired them theamata (‘sights’), but this soon evolved to the grander name of thaumata – ‘wonders’.

Why are there only seven wonders?

The Seven Wonders we know today are an amalgamation of all the different lists from antiquity. The best-known versions come from the second-century-BC poet Antipater of Sidon, and mathematician Philo of Byzantium, but other names include Callimachus of Cyrene and the great historian Herodotus. What made their list relied on where they travelled and, of course, their personal opinion, so while we recognise the Lighthouse of Alexandria as a Wonder today, some left it out, favouring the Ishtar Gate of Babylon instead.

But why are there only seven? Despite a plethora of structures and statues in the ancient world worthy of inclusion, there have only ever been seven Wonders. The Greeks chose this number as they believed it held spiritual significance, and represented perfection. This may be as it was the number of the five known planets at the time, plus the Sun and Moon. And another question about the Seven Wonders, considering all but one are long lost or destroyed, may be – what exactly are they?

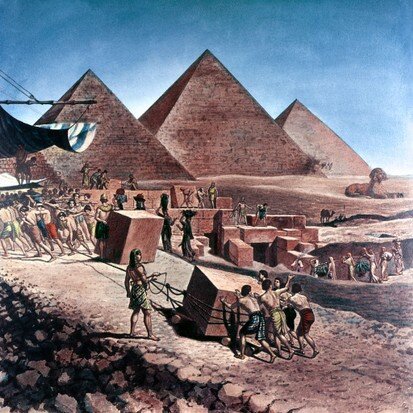

Great Pyramid of Giza

Get a room full of people to name the Seven Wonders and most would name the Great Pyramid of Giza first. The reason is simple enough – while the other six have been lost for centuries, the Great Pyramid of Giza still stands proudly in northern Egypt.

Built in c2500 BC as the tomb of the fourth-dynasty pharaoh Khufu, it is the largest of the three Giza pyramids. Its original height of 146.5 metres (481 feet) made the pyramid the tallest human-made structure in the world until Lincoln Cathedral eclipsed it in the 14th century. The years have seen the outer layer of limestone erode – cutting almost eight metres (27 feet) off the height – but the pyramid remains one of the most extraordinary sights on the planet. Recent estimates suggest that it took around 14 years to transport and place the 2.3 million stone blocks.

Just how the pyramids were built – or how, 4,000 years ago, Egyptians aligned their structures with the points of the compass – remains the subject of debate.

Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

Over the course of his life, the powerful Mausolus built a magnificent new capital for himself and his wife Artemisia at Halicarnassus (on the western coast of modern-day Turkey), sparing no expense to fill it with beautiful marble statues and temples. There was no question that he, being the satrap (governor) of the Persian Empire and ruler of Caria, would enjoy similar luxury after he died in 353 BC.

Artemisia (also Mausolus’s sister) was supposedly so grief-stricken by her husband’s death that she mixed his ashes with water and drank them, before overseeing the building of his extravagant tomb. Made of white marble, the monumental structure sat on a hill overlooking the capital he had built.

Artemisia was supposedly so grief-stricken by her husband’s death that she mixed his ashes with water and drank them, before overseeing the building of his extravagant tomb

It had been designed by Greek architects Pythius and Satyros and boasted three levels – combining Lycian, Greek and Egyptian architectural styles. The lowest was around 20 metres (66 feet) high, forming a base of steps that led to the second level, ringed by 36 columns. The roof was in the shape of a pyramid, with a sculpture of a four-horse chariot on top bringing the height of the tomb to around 41 metres (135 feet). Four of Greece’s most renowned artists created other sculptures and friezes to surround the tomb, each decorating a single side.

The tomb may have been destroyed by earthquakes in medieval times, but a part of it lives on to this day – such was the splendour of Mausolus’s final resting place that his name led to the word ‘mausoleum’.

Statue of Zeus

Olympia – a sanctuary in ancient Greece, the site of the first Olympic Games and the home to a Wonder. And what better way to respect the chief god of the Ancient Greeks than to build a giant statue of him? That’s what sculptor Phidias did when he erected his masterpiece at the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, in c435 BC.

Zeus sat resplendent on a throne made of cedar wood and decorated with gold, ivory, ebony and precious stones. The god of thunder held a statue of Nike, the goddess of victory, in his outstretched right hand and a sceptre with an eagle perched on top in his left. He was further adorned with gold and ivory, meaning that the temple priests had to oil the statue regularly to protect it from the hot and humid conditions of western Greece. Such was the size of the statue, almost 12 metres (39 feet) high, that it barely fitted inside the temple, with one observing, “It seems that if Zeus were to stand up, he would unroof the temple.”

For eight centuries, people would voyage to Olympia just to see the statue. It survived Roman emperor Caligula, who wanted it brought to Rome so that its head could be replaced with his own likeness, but Zeus was eventually lost. It may have happened with the destruction of the temple in AD 426, or been consumed in afire after being transported to Constantinople.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Detailed descriptions may exist in many ancient texts, both Greek and Roman, but no other Wonder is more mysterious than the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

All accounts, after all, are secondhand, and there is still no conclusive evidence that they existed at all. If they were real, they demonstrated a level of engineering skill way ahead of its time, as keeping a garden lush and alive in the deserts of what is now Iraq would have been no small feat.

One theory is that the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II had the Hanging Gardens created, in c600 BC, to help his homesick wife, who missed the greenery of her Median homeland (what is now Iran).

They may have been an ascending series of rooftop gardens, with some of the terraces supposedly reaching a height of around 23 metres (75 feet). This gave the impression of a mountain of flowers, plants and herbs growing out of the heart of Babylon. The exotic vegetation would have been irrigated by a sophisticated system of pumps and pipes, bringing water from the Euphrates river.

Philo of Byzantium describes the process of watering the gardens: “Aqueducts contain water running from higher places, partly they allow the flow to run straight downhill and partly they force it up, running backwards, by means of a screw,” which includes an early ‘Archimedes Screw’. “Exuberant and fit for a king is the ingenuity, and most of all, forced, because the cultivator’s hard work is hanging over the heads of the spectators.”

It has been postulated that the Hanging Gardens did exist, but not in Babylon. Dr Stephanie Dalley of the University of Oxford claimed that the gardens and irrigation were the creation of the Assyrian king Sennacherib for his palace at Ninevah, 300 miles to the north and on the Tigris river.

Lighthouse of Alexandria

Boats sailing into the harbour of Alexandria found it a tricky prospect, thanks to shallow waters and rocks. A solution was needed for the thriving Mediterranean port (on the coast of Egypt) – founded by Alexander the Great in 331 BC, hence the name – and it came in the shape of a lighthouse on the nearby island of Pharos.

Greek architect Sostratus of Cnidus was handed the job, which took well over a decade, with construction finished in the reign of Ptolemy II, c280-70 BC. It is thought that the lighthouse reached a height a little under 140 metres (459 feet), making it the second-tallest human-made structure of antiquity behind the Great Pyramid of Giza. The tower was divided into a square base, an octagonal midsection and a cylindrical upper section, all connected by a spiral ramp so that a fire could be lit at the top.

This was allegedly visible 30 miles away. Greek poet Posidippus described the sight: “This tower, in a straight and upright line, appears to cleave the sky from countless stadiums away… throughout the night, a sailor on the waves will see a great fire blazing from its summit.” This design became the blueprint for all lighthouses since.

Like some of the other Seven Wonders, the lighthouse fell victim to earthquakes. It managed to survive several major shocks, but not without heavy damage that led to it being abandoned. The ruins collapsed for good in the 15th century. That wasn’t the last of the lighthouse, however, as French archaeologists discovered massive stones in the waters around Pharos in 1994, which they claim formed part of the ancient structure. Then in 2015, Egyptian authorities announced their intention to rebuild the Wonder.

Temple of Artemis

You may have an opinion on what was the greatest Wonder, but few were more certain than Antipater of Sidon. His tribute to the Temple of Artemis read: “I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon on which is a road for chariots, and the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus, and the Hanging Gardens, and the colossus of the Sun, and the huge labour of the high pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolus but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy, and I said, ‘Lo, apart from Olympus, the Sun never looked on aught so grand’.”

...when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy

Antipater of Sidon

That said, the temple had a difficult, violent existence, so much so that there were actually several temples, built one after the other in Ephesus, modern-day Turkey. The Wonder was repeatedly destroyed by a seventh-century-BC flood, an arsonist named Herostratus in 356 BC, who hoped to achieve fame by any means, and a raid by the East Germanic Goths in the third century. Its final destruction came in AD 401. Very little remains of the temple, save for fragments held by the British Museum.

At its most impressive – the version that inspired Antipater’s account – the white marble temple ran for over 110x55m (361x180ft), with its entire length ornamented by carvings, statues and 127 columns. Inside stood a statue of the goddess Artemis, a site of homage for the many visitors to Ephesus, who left offerings at her feet.

Colossus of Rhodes

Erected c282 BC, the Colossus of Rhodes was the last Wonder built, and among the first destroyed. It stood for less than 60 years, but that didn’t signal the end of its status as a Wonder.

The mighty statue of the sun god Helios had been erected over 12 years by the sculptor Chares of Lindos to celebrate a military triumph in a year-long siege. Legend claims that the people of Rhodes sold the tools left by their vanquished foe to help pay for the Colossus, melted down abandoned weapons for its bronze and iron edifice, and used a siege tower as scaffolding.

Overlooking the harbour, Helios stood at 70 cubits – some 32 metres (105 feet) – high, possibly holding a torch or a spear. Some depictions show him straddling the harbour entrance, allowing ships to sail through his legs, but this would have been impossible with the casting techniques of the time.

Regardless, the Colossus still wasn’t strong enough to withstand an earthquake in 226 BC, and the statue came crashing to the ground in pieces. Rhodians declined Ptolemy’s offer to have it rebuilt, having been told by an oracle that they had offended Helios.

So the giant, broken sections lay on the ground, where they stayed for over 800 years still attracting visitors. The historian Pliny the Elder wrote: “Even as it lies, it excites our wonder and admiration. Few people can clasp the thumb in their arms, and its fingers are larger than most statues.” When enemy forces finally sold the Colossus for scrap in the seventh century, it took 900 camel loads to shift all the pieces.

Source: HistoryExtra