Greece sits at the crossroad between the Eastern and Western cultures of Asia and Europe. Being at this critical junction, Greece has experienced the ebb and flow of two cultural currents which subjected and allowed her to assimilate creatively diverse influences. Once Constantinople fell in 1453, completing the collapse of the Byzantine empire, there followed four hundred years of slavery which greatly hindered the natural development of Hellenism and restricted its spiritual evolution.

This period was particularly harsh and had an inhibitive influence on Greek music. From the twelfth or thirteenth century forward, an economically exhausted Byzantium was slowly collapsing due to years of factional rebellion, religious disputes, western crusades and eastern invasions. While the new technique of polyphony was developing in the West, the Eastern Orthodox Church resisted any type of change. Therefore, Byzantine music remained monophonic and without any form of instrumental accompaniment. As a result, Byzantine music was deprived of polyphony and instrumental accompaniment, elements of which in the West encouraged an unimpeded development of art. This inspired the development of a musical structure that eventually resulted in the music of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven.

However, the isolation of Byzantium, which kept music away from polyphony, along with centuries of continuous culture, enabled monophonic music to develop to the greatest heights of perfection. Byzantium presented us with a melodic treasury of inestimable value for its rhythmical variety and expressive power; the monophonic Byzantine chant. Along with the Byzantine chant, a form of artistic musical creation, the Greek people also cultivated the folk song.

The Origins of Greek Folk Song

The origins of the Greek folk song can be traced back to the first centuries of Christianity due to the orchestric and pantomimic performances that prevailed after the third century A.D. As early as the first century A.D., ancient Greek tragedy, which at its peak of harmonious unity, incorporated poetry, music and dance, had disintegrated into its component elements.

Actor-tragedians continued to perform only certain parts of the dialogue of the tragedies, while others with good voices sang the vocal parts. There also arose a gesticulator whose purpose was to illustrate, with pantomimic gestures, what the actor-tragedian was singing. This gradually transformed the old Attic style of tragedy and comedy into the tragic-pantomime style of the imperial Byzantine years that included dance, mime, recitation and song. The reactions of the Church Fathers and the stream of condemnatory decisions and excommunications issued by ecumenical synods indicate the popularity of these spectacle-concerts in multi-ethnic Byzantium and the influence of the mime performances on the austere moral code of the Christians for many centuries to come.

The tragic pantomime, however much a product of troubled times and adapted to what the ill-educated masses wanted to see, preserved many elements of Greek poetry. The word paraloghi (narrative song or ballad) probably originates from the ancient Greek parakataloghi, a form of musical recitation somewhere between recitation and ode (pure melody). Further evidence of the relationship between folk song and ancient Greek poetry and music is the derivations of the folk words traghoudl (song) and traghoutho (to sing) from ancient traghodia (tragedy) and traghodho (to act).

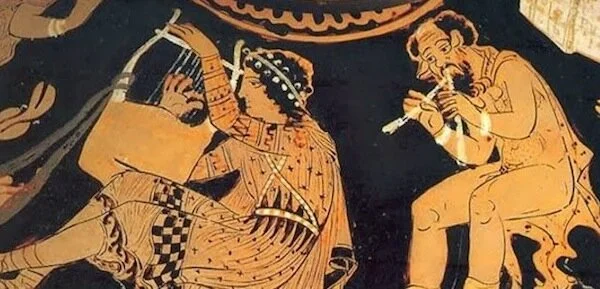

Musicological research has unearthed valuable evidence linking modem Greek folk song to ancient Greek music. It is not feasible to compare these musical types due to the influence of Christianity. Also, there is a substantial difference between ancient Greek prosody (quantitive), a recitation which clearly marked the difference between long and short syllables; thanks to its vowels, each word had an elementary rhythmic form as well as a rough melodic fine. In contrast, modem Greek is based on a tonic prosody (strong accentuation); its words simply have accentuated or non-accentuated syllables. Despite the change from quantitative to tonic prosody, the ancient Greek rhythmical formations live on in modem Greek folk melody. The researches of Professors Thrasyvoulos Georgiadis and Samuel Baud-Bovy demonstrate that the 7/ 8 time, found throughout Greece, in none other than the heroic hexameter in which the Homeric epics were recited. The word syrtos is known to have existed as early as the first century A.D., from an ancient Greek inscription. In addition, dance formation representations on vases, statuettes and terracottas show dancers linked either hand-on-shoulder or hand-in-hand with the instrumentalist in the center

Greek Folk Songs

The Greek folk song can be divided into two cycles, the akritic and klephtic. The akritic was created between the ninth and tenth centuries A.D. and expressed the life and struggles of the akrites (frontier guards) of the Byzantine empire, the most well known being the stories associated with Digenes Akritas. The klephtic cycle came into being between the late Byzantine period and the start of the Greek War of Independence struggle in 1821. The klephtic cycle, together with historical songs, paraloghes, love songs, wedding songs, songs of exile and dirges express the life of the Greeks. There is an indivisible unity between the Greek people's struggles for freedom, their joys and sorrow and attitudes towards love and death. There is, however, a difference between dhimotiko traghoudhi (folk song) and laiko traghoudhi (popular song). A "folk song" refers to the old songs of a given people; whereas, a "popular song " refers to more recent musical creations. Folk songs refer to all songs created before the 1821 War of Independence, which belong to the akritic and klephtic cycle.

The same two terms apply to Greek musical instruments. The lira, laouto (lute), tambouras, gaida (bagpipe), zoumas (shawm), daouli (drum) belong to the category of folk instruments. The violin, clarinet and guitar belong in the popular category. Although assigning the year 1821 as a measure to divide "folk" from "popular" songs is an arbitrary methodological delineation, the ultimate criteria for assigning individual songs to one or the other category is entirely literary and musical.

Greek folk song, either diatonic or chromatic, like Byzantine music, is monophonic and modal in structure. In other words, without any harmonic accompaniment its melodies are based on a different sequence of intervals than that of the major and minor modes of Western music. As is true of any monophonic music, the Greek folk song is performed on the natural rather than on the Western tempered scale. Certain songs of northern Epirus, sung in polyphony without any instrumental accompaniment, constitute an exception to the bulk of Greek monophonic and modal folk songs. A form of "primitive two-voice singing" is also encountered in certain songs from Karpathos. These songs, where one sings melody and the other takes up a vocal drone, is symptomatic of the tsabouna (island bagpipe).

From the point of rhythm, the Greek folk song is divided into the periodical and free rhythmic types. The periodical is characterized by a free flow of various rhythmic patterns (table songs) while the free rhythmic is characterized by the periodic repetition of a given rhythmical formula (dance tunes).

Along with singing and clapping, the Greek people have since early times used every available combination of instruments to provide the musical accompaniment for their singing and dancing. Apart from any chance combinations dictated by the moods of the revellers and instruments at hand, certain instrumental combinations attained the status of ziyia (paired groups); the pear-shaped Macedonian lira and the large dachares (tambourine), violi and laouto on the islands and the zourna and daouli. It is to popular musicians who play instruments suitable for open-air village fairs that the Greek owes his sense of traditional music. Those self-taught players bore upon themselves the entire weight of Greek musical tradition not only of the performer, but also of the instrument maker. More often than not, the players performed on instruments of their own manufacture. A good player's instrument remains under continuous manufacture; he not only adds, removes or alters a spare part but constantly endeavors to improve the sound of his instrument. Hence, the great differences found in the dimensions, decorations and even shapes of their instruments; each bearing the personal stamp of its player / maker.

Along with individual player/instrument makers there existed several workshops where musical instruments were made. These shops began to appear in the second half of the nineteenth century first in Athens, Piraeus and then later in Thessaloniki, especially 1922 when Greece saw an enormous influx of musicians and instrument makers from Asia Minor. Increasing demand kept the shops busy producing instruments like the outi (oud), laouto, tamboura, bouzouki, baglama, dzoura, etc. Instrument manufacturing in these shops reached its zenith between 1900-1940. These craftsmen provided instruments to popular players who traveled from village to village and region to region keeping the folk melodies alive. In addition, some shops also made mandolins, guitars, mandolas and mandolocellos which gave rise to the musical art form of groups called "mandolinata".

Gypsies have always held a special place in the musician's world. Early on, locals would not stoop to the profession of musician, thus instrumental music fell into the hands of gypsies. As musicians, gypsies decisively influenced the evolution of an instrument style as well as, in some instances, the structure of folk melody Gypsies were also responsible for the frequent change in a given melody from a diatonic to a melodic style.

In passing on Greek musical traditions, the relationship between a teacher and his pupil acquired a special significance. According to old tradition, pupils paid a monthly sum determined by the skill of the teacher. In some regions, it was also customary for the pupil to board at the teacher's home, where he paid for room and board. The lessons were not structured like modem teaching methods. There were no music books provided or explanation of style of technique. The teacher had nothing to say; he did not speak, he just played. The pupil would sit and listen and try to imitate the teacher or "steal" his technique. -Learn how to steal" was the advice given by a teacher, and it was this ability to which the pupil derived the benefits from paying tuition. Teachers also jealously kept the "secrets" of their art to themselves; he would never let himself go or play freely for his pupils. He always kept in mind that today's untried pupil would be tomorrow's competition. I will illustrate how a pupil would become a zourna player. The teacher would take him along to festivals in order to make use of the pupil's assistance (for free). The pupil starts by playing the ison (drone note) in accompaniment with the teacher. By degrees, he begins to reproduce certain simple end phrases and easy tunes in unison with his teacher until he feels competent to carry out a single melody on his own, at which time the teacher could light a cigarette or take a short rest. This is the point in their relationship where the pupil may start to learn some of the secrets of the master, as the master now feels free to play without restraint. The pupil will finally start to feel like a professional when the teacher earmarks a portion of the evening's earnings for him.

Popular Songs

Some of the recent urban popular songs include the Heptanesian cantatha, Athenian cantatha and rebetika. The Heptanesian cantatha (in major and minor modes of Western music) is usually sung by three male voices in chorus, characterized by simple harmonic improvisations and accompanied by guitar, mandolin or other similar instruments. Although Italian music greatly influenced this serenading type of music with its sweet, nostalgic melody and romantic words based primarily on love, it originated in Kephalonia. at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Its popularity caused it to spread rapidly to other Ionian islands, especially Zakynthos and Kerkyra before eventually reaching the mainland of Greece.

The Athenian cantatha, which came into existence at the end of the nineteenth century was also affected by Italian music and flourished along with the rage for Italian melodrama in Athens. The Heptanesian cantatha also influenced the Athenian cantatha after the union of the Ionian islands with Greece in 1823. These folk melodies, still sung by Greek people as though they were true folk songs, are accompanied by the island zigla (violin and laouto) or by a compania (violin, clarinet, santouri and laouto).

The rebetiko song emerged in urban centers throughout Greece, especially those with large harbors, and appealed to a restricted audience of convicts, dock workers, hashish and narcotics users, the "down and out" segment of today's society. The rebetiko song is often gloomy and fatalistic in content and was always sung by a single voice. Its popularity increased until embraced by the majority of the working class, reaching its classical period in the years between 1940-1950. The principal instruments of rebetiko were the bouzouki, baglama, and guitar.

At that period, the words of the rebetiko songs touched on the times and stirred up people's longings for escape and love. The classic rebetiko songs were distinguished for their sincerity of passion and power of expression. Within the music style, one can detect the contributions and influence of folk song, Byzantine chant, and music of the East. Gramaphone recordings carried rebetika to the remote villages in Greece, gradually displacing the traditional folk song in the process.

Most of the rebetiko composers never studied music; whatever rudimentary musical knowledge they possessed was the result of the considerable experience they acquired professionally. Naturally gifted, they composed their melodies by playing them on their respective instruments. When songs were published, the musical notation was undertaken on their behalf by a musically educated person.

Folk melody was transmitted orally from one generation to another and was constantly reworked. Its perfection of form was due to long centuries of cultivation and processing. However, the cantatha and rebetiko was never subject to this type of processing; it adheres to the laws governing artistic composition in establishing and transmitting itself. The form by its creator is imposed on all through musical notation and via modern mass communication media (gramaphone recordings, radio and television),

Modern Greek Folk Song

The Second World War, German occupation of Greece and the Greek Civil War decisively influenced the Greek folk song. People's hunger for "light music" dealt the folk song a crushing blow and forced it into its final stage of development. After the first World War and the 1922 debacle, the trend towards urban living focused on Athens where popular musicians congregated and, in 1928, founded their own professional society: the Athens and Piraeus Musicians Society.

Until the early years of this century, musical tradition was preserved in the villages where there was little contact with the outside world.

The events and social changes of the twentieth century (The Balkan Wars, Asia Minor disaster, Western music via the gramaphone, radio and television) decided the fate of the folk song in Greece. Once the seat of folk song was the village, where the music was disseminated to the towns; now the reverse applies. Now the commercialized folk song spreads in all directions to the remotest villages. The authentic songs and dances the villagers have enjoyed since their youth have been replaced by the stylized modem "folk songs" written by contemporary musicians. They write new lyrics to authentic folk tunes, changing them enough to ensure copyright protection for themselves and reap the handsome profits that accompany their efforts.

The Study of Greek Folk Song

The study of Greek folk song is a relatively recent development. After the liberation of Greece from Turkish rule and the formation of the modem Greek state, Greek intellectuals devoted their efforts to studying ancient Greece and its civilization. Between King Otto bringing his Bavarian band to Greece in 1934 and the constant waves of Italian melodrama groups from 1840-1900, Greek urban listeners began to associate their monophonic folk music with the tortured centuries of slavery (1453-1821). In comparison with the polyphonic Western music, they felt their music was "poor" and gradually drew away from their music tradition. In fact, the Greek upper social strata and intellectuals turned to the music of Bach and Beethoven, looking with indifference or even contempt on their native folk music. To date, Greek folk song has never been systematically included in school curricula, not taught in Greek conservatories, nor is there a chair of musicology in any of the Greek universities.

The earliest efforts to research, collect and publish Greek folk songs was done by foreigners. The first comprehensive musical collection was published in Paris in 1876 by L.A. Bourgault-Ducoudray. However, the Europeans only designated the principal notes of each melody and omitted the distinctive grace notes, trills, glissandi, pauses, etc. One must remember that "Greek folk song" combines the indivisible unity of lyrics, music and dance. The union of words, music and dance is encountered in daily life when a mother sings tachtarismata (melodies) of simple words while bouncing her child on her knees in time to the music. The same holds true for nanourismata (lullabies) where the gentle rocking of the child and the mother's footsteps, itself a type of gentle dance step, combined rhythmically with the melody sung to put die child to sleep. In miroloyia (dirges), women who gather to keen over corpses perform certain movements in time with the rhythm of the dirge tune, rocking their bodies, shaking their heads which grows in intensity as the hours pass. In Greece, the founder of rigorous ethnomusicological scholarship and research into the folk song was the neo-Hellenist scholar Professor Samuel Baud-Bovy. Thanks to his studies, transcriptions and publications, Greece occupies a position among the family of nations in this branch of study.

Contributed by Nicholas Zallas

Odyssey Orchestra

source: Hellenic Communication Service