The Cossacks’ Journey from Autonomy to Ottoman Service

Throughout the Tsarist Empire, various Cossack communities had secured a degree of self-governance. However, by 1707, their privileges began to erode, leading to rebellion. Many Cossacks, either fleeing the Tsar’s persecution or seeking revenge, abandoned their homeland and offered their services as mercenaries to the Ottoman Sultan.

A large group of Cossacks soon joined the ranks of the Ottoman military, and for a time, the Russian Empire attempted to restore stability by reinstating their autonomy. But when Empress Catherine the Great rose to power, she revoked their privileges and sent General Potemkin to bring them under control.

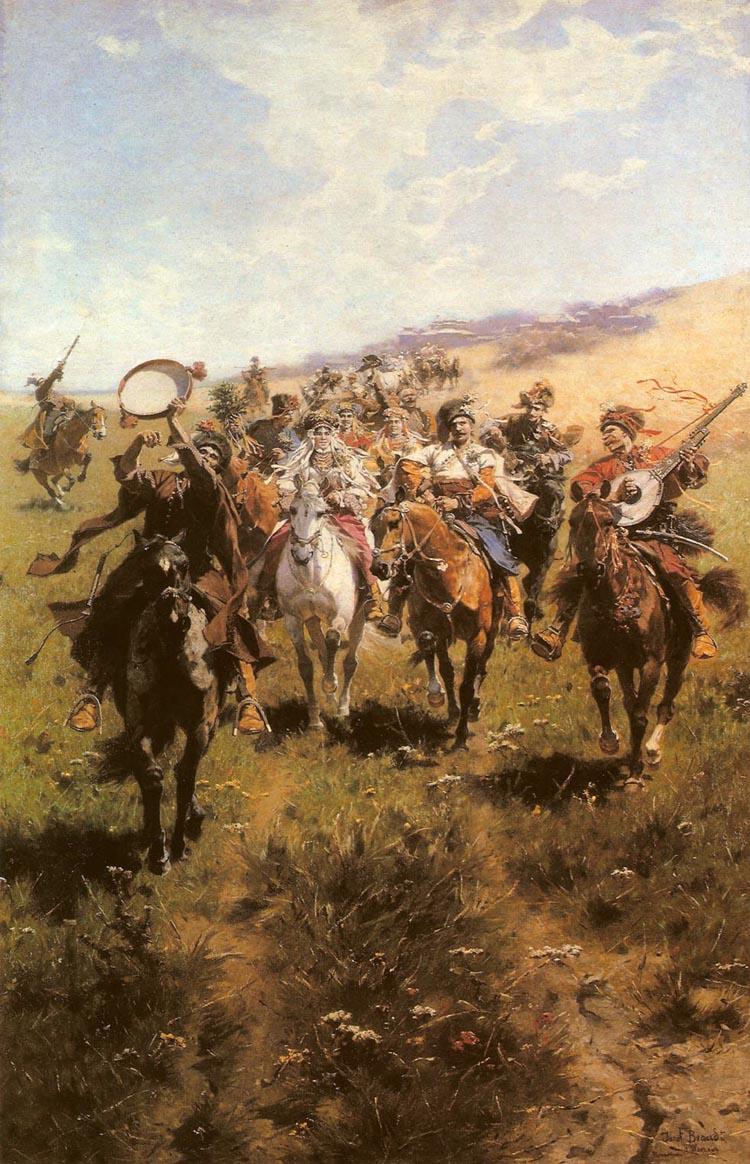

Once again, the Cossacks rebelled. Five thousand of them swore allegiance to the Sultan, becoming cavalrymen in the Ottoman army. Over time, more Cossacks joined, and the Ottoman military eventually gained a formidable force of 10,000 elite horsemen—widely regarded as some of the best cavalrymen of the time.

Cossacks Against the Greeks: The Siege of Messolonghi

Cossacks Against the Greeks at Messolonghi

The Ottomans wasted no time in deploying their new Cossack forces against rebellious nations, including the Greeks. When the Greek Revolution broke out in 1821, Cossack cavalry was sent to suppress the uprising, beginning with the Battle of Sculeni in Moldavia.

The Cossacks attacked with relentless fury, crushing the Greek revolutionaries before turning their wrath upon the town itself. When the residents of Sculeni realized that their attackers were fellow Orthodox Christians, they desperately held up church crosses, icons, and priests in a plea for mercy. But the Cossacks showed no compassion.

Their leader, Osip Gladky, was particularly ruthless. For his brutality against fellow Christians, the Sultan rewarded him with the title of Pasha and specifically assigned him to campaigns against Christian populations. Gladky soon became an even greater enemy of the Greeks than the Turks themselves.

At the siege of Messolonghi, it was his Cossacks who carried out the worst of the massacres during the Greeks’ desperate sortie from the besieged city.

From Fighting Greeks to Fighting Turks

In 1828, after negotiating with Tsar Nicholas I, Osip Gladky and his Cossacks were allowed to return to Russia. His cavalry split into two groups—one traveling overland with him, while another, led by a commander named Moraz, secured passage back by sea aboard a Turkish vessel.

Gladky’s men, arriving first by land, were welcomed back as heroes. The Russian authorities seemed unconcerned by the massacres the Cossacks had committed against fellow Orthodox Christians during their service under the Sultan. Perhaps in an attempt to atone, Gladky went on to wage bloody campaigns against the Ottomans during the Russo-Turkish War, exhibiting the same ruthless enthusiasm he had once shown against the Greeks.

For his loyalty, the Tsar honored him with the rank of general, much like the Sultan had once named him a Pasha. As a reward, he was also granted vast tracts of land.

A Stroke of Fate: The “Divine” Punishment

Just as it seemed that Gladky and his men would enjoy their new status in peace, fate took a cruel turn. A cholera outbreak swept through their ranks, killing many of them.

The Fate of Moraz’s Cossacks

Meanwhile, the Cossacks who had chosen to return to Russia by sea did not fare much better. Numbering around 600, they boarded a large Turkish ship, but as they passed Cape Tenaro, Greek Admiral Andreas Miaoulis and his fleet intercepted them. The Greek navy attacked the Ottoman convoy, setting fire to several ships—including the one carrying the Cossacks.

Many Cossacks burned to death on board, while others drowned, unable to swim. Those who survived were captured by the Hydriots and imprisoned in a monastery on the island of Hydra.

Seeking Pardon in Hydra

The Fate of Moraz’s Cossacks

Facing imprisonment and uncertain fate, the Cossacks who had once mercilessly slaughtered Greeks at Sculeni and Messolonghi now remembered their Christian faith. They wrote a desperate plea to the Patriarch of Constantinople, appealing to their shared religion and requesting mercy.

Moved by their plea, the Patriarch intervened with the Greek authorities, who ultimately agreed to release them. Some of these Cossacks chose to remain on Hydra permanently, seemingly forgiven by the local population. Over time, they lived out their lives there, and their graves were once a notable feature of the island’s cemetery.

Thus ended the story of the Cossacks who had fought both for and against Christians, shifting allegiances between Tsars and Sultans, only to find themselves at the mercy of the very people they had once fought against.