Living the Ancient Greek Death

By Robert Garland, Ph.D., Colgate University

One needs to put oneself in the sandals of a dying Greek to understand the mind frame of the ancient Greeks and to understand why they did the things that they did. Also, one needs to live an ancient Greek death following all the rites of passage and the burial laws.

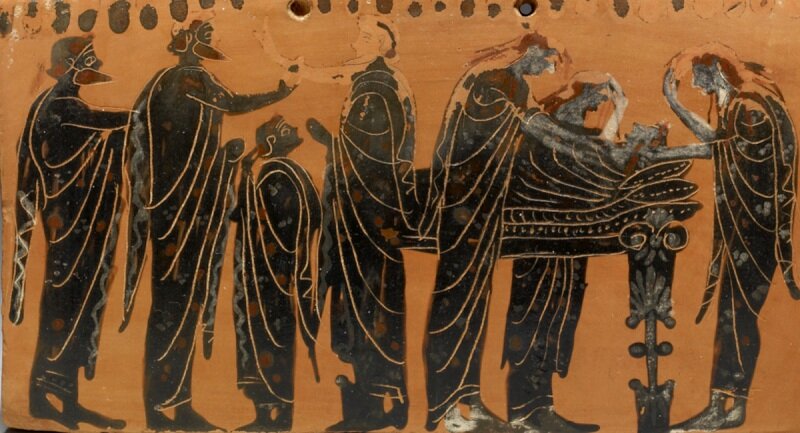

The first rite of passage, or prothesis, means laying out of the body. (Image: Walters Art Museum/Public domain)

Putting Oneself in the Sandals of a Dying Greek

The ancient Greeks held certain ideas about death. One of the most characteristic motifs that people find on ancient Greek tombstones is the handshake between the living and dead. Both figures invariably exhibit a dignified calm. That’s what Greek tragedy is all about—looking death squarely in the eye. As a Greek, they knew that terrible things happen; and they knew, too, that by confronting them head-on, they’d be able to deal with them and get on with life. One could posit that the Greeks got it just right.

But one needs to put oneself in the sandals of a dying Greek to understand it. It’s an unpleasant thought, but there’s no escaping it if one wants to fully experience the other side of history.

The Role of a Physician in Death

Let’s assume one is dying in one’s home, surrounded by one’s relatives, including young children. There won’t be any physician at hand to give painkillers.

A physician may have offered treatment in the earlier stages of sickness, but once it became inevitable that there could only be one outcome, the medical profession had nothing to offer anymore.

It’s also extremely unlikely that a physician would be called in to put one out of one’s misery by euthanasia, a coined word of Greek etymology meaning ‘good death’, but which has no ancient Greek equivalent. In fact, the Hippocratic Oath, which was probably widely adopted, enjoined upon those physicians who took it “not to administer a poison to anybody who asked for one and not to propose such a course”. So let’s hope that one’s final illness is short and painless.

The Role of Gods in Death

The poet Keats has a wonderful line in Ode to a Nightingale: “I have been half in love with easeful death”. The Greeks conceived of easeful death in the form of the God Apollo, who came to strike them down with his so-called ‘gentle arrows’. That’s the best that he or any other of the gods had to offer. They certainly didn’t have any consolation to give someone.

In Euripides’ play the Hippolytus, when Hippolytus is dying, the goddess Artemis, to whom he has devoted himself exclusively all his life and with whom he’s had a very close relationship, bids him farewell. She explains to him that it’s not lawful for a deity to be present at the death because the pollution that a corpse releases would taint her.

The one god who may have taken some slight interest in the fate of the dying is the healing God Asclepius. When Socrates passes from this world to the next in Plato’s dialogue the Crito, he has this to say, “I owe a cock to Asclepius. See that it’s paid.” Cocks were sacrificed to Asclepius. Socrates may be indicating that Asclepius eased his passing, although it’s possible, too, that he’s merely suggesting philosophically that death is a ‘cure’ for life.

The First Rite of Passage: Prothesis

in ancient Greece, as soon as one died, the women in one’s family began keening and ululating so that everyone in the neighborhood knew of the individual’s demise. It was the women, too, who took charge of one’s body and prepared it for burial. They closed one’s mouth and eyes, tied a chin strap around one’s head and chin to prevent the jaw from sagging; they washed the whole body, anointed it with olive oil; they clothed the body and wrapped it in a winding sheet, leaving only one’s head exposed.

Then they laid the body on a couch with one’s head propped up on a pillow and one’s feet facing the door. After getting all this done, they sang dirges in one’s honor.

This is the scene that is depicted on the very earliest Greek vases with figurative decoration. It’s called the prothesis, which literally means the laying out of the body. It represents the first stage in the process that will take one from this world to the next, ‘from here to there’, as the Greeks put it. Meanwhile, relatives and friends would call at the house and join in the grieving.

The Second Rite of Passage: Ekphora

The second rite of passage is the ekphora. Ekphora means literally ‘the carrying out of one’s body’—specifically from one’s home to one’s place of burial. According to Athenian law, the ekphora had to take place within three days of one’s death, although in hot weather it’s likely that it would have taken place much sooner. The ekphora had to take place before sunrise so that it wouldn’t create a public nuisance.

If one was wealthy, one’s body would be transported in a cart or carriage drawn by horses. This scene is also depicted on the earliest vases with figurative decoration. Professional undertakers might also be employed to bear the corpse and break up the ground for burial. These professionals were known as ‘ladder men’ klimakophoroi, because they’d lay one’s body on a ladder, which they carried horizontally.

If professional undertakers were employed, they wouldn’t have any physical contact with the family members before this phase. The Greeks would have been shocked and appalled by the idea of handing over one’s body to professionals to prepare it for burial.

Pottery was one of the most

common grave gifts for the dead. (Image: British Museum/Public domain)

The Third Rite of Passage: Burial

It was one’s relatives who conducted the burial service. No priests were present either. Priests were debarred for exactly the same reason that Artemis absented herself from the dying Hippolytus, so as not to incur pollution. Because if they incurred pollution, they might transmit it to the gods.

Absolutely nothing is known about the details of the burial service. Truth be told, it’s not even known if there was a burial service as such. If any traditional words were spoken, they were not recorded. Both inhumation and cremation were practiced, although cremation, being more costly, was seen as more prestigious. If one was cremated, then one’s relatives would gather the ashes and place them in an urn, which they then would bury along with the grave gifts.

The commonest grave gift was pottery. In fact, that’s why so many high-quality Greek vases have survived intact—because they were placed intact in the ground.

Over time, however, the Greeks became more stingy. Chances are, if one died in the 4th century B.C., all one would get is a couple of oil flasks known as lêkythoi filled with olive oil—olive oil was regarded as a luxury item. Some Greeks, however, were so stingy that they purchased lêkythoi with a smaller internal container to save them the expense of filling the whole vase with oil. Supposedly, they thought the dead wouldn’t notice.

As soon as the filling of the grave was done, they’d erect a grave marker over it. After completing the third and final rite of passage, all the mourners would return to the grieving home for a commemorative banquet.

The Burial Laws

Since one’s corpse was regarded as a source of pollution—the Greek word for the pollution is miasma, which means much the same in English—one had to be buried outside the city walls. In the ancient Greece, burial within a settlement was extremely rare after the 8th century B.C. The same was true of Rome. The earliest Roman law code, the Law of the Twelve Tables, dated 450 B.C., contains the provision, “The dead shall not be buried or burnt inside the city.”

It is not certain, but the origins of the belief in pollution may be connected with a kind of primitive sense of hygiene. Dead one’s relatives and anyone else who had come into contact with the corpse were debarred from participation in any activities outside the home until the corpse had undergone purification.

Reintegration into the community for mourners didn’t take place until several weeks after the funeral. One’s relatives also had to take measures to prevent the polluting effect of one’s corpse from seeping into the community. That included providing a bowl of water brought from outside the house so that visitors could purify themselves on leaving.

Common Questions About Living the Ancient Greek Death

Q: What are the three stages of an ancient Greek funeral?

The three stages are the laying out or the prothesis, the funeral procession or the ekphora, and the burial or the Interment.

Q: How did the Greeks honor the dead?

Greeks honored the dead by following the three rites of passage, by building the tombs in Ceramicus, the Potter’s Quarter, and by offering the grave goods.

Q: How did Greeks prepare for the afterlife?

Greeks prepared for the afterlife by following the three rites of passage and offering the grave goods.

Q: What was the burial law in ancient Greece?

According to the burial law in ancient Greece, one had to be buried outside the city walls.

Source: thegreatcoursesdaily