The eruption of the Santorini volcano: When fire and ash swallowed a thriving civilization.

Before becoming one of the world’s most famous volcanic ruins, Santorini (Thira) hosted a flourishing Bronze Age civilization. The settlement of Akrotiri on the island was a thriving hub of trade, art, and urban complexity, heavily influenced by the powerful Minoan civilization.

By 2000 BCE, Akrotiri had transformed into a highly developed city featuring:

Multi-story buildings with flat roofs and wooden columns resembling Minoan architecture.

An advanced drainage system with indoor toilets.

A trade network extending from the Aegean to Egypt and the Near East, as evidenced by imported pottery, seals, and raw materials like ivory and ostrich eggs.

Vibrant frescoes covering entire rooms, depicting nature, rituals, and exotic animals like monkeys and antelopes.

Strategically located on the maritime trade route between Cyprus and Crete, Akrotiri thrived as a metallurgical center, as evidenced by furnaces, bronze molds, and tools discovered during excavations.

However, by 1650-1550 BCE, nature would claim dominion with an eruption so massive that its effects reached far beyond the Aegean.

The Day of the Eruption:

Image Source: Santorini Caldera

The studied evidence shows that before the main eruption, significant seismic activity and warning signs occurred. On the day of the destruction, the island shook with earthquakes measuring 7 on the Richter scale, collapsing structures before the volcano itself erupted in a series of dramatic stages:

The Volcano Erupts: Violent explosions sent massive amounts of pumice and ash into the air, with a cloud of ash and gas rising 30-40 kilometers.

Caldera Collapse: The emptying of the magma chamber caused the central part of the volcano to collapse, forming a caldera. This collapse triggered massive tsunamis that impacted nearby coastlines.

Pyroclastic Flows: The ensuing pyroclastic flows, a mixture of hot gases, ash, and volcanic rocks, swept across the island, destroying everything in their path. The Akrotiri settlement in Santorini was buried under a thick layer of volcanic material. Archaeological evidence suggests that the inhabitants had evacuated before the final destructive phases.

A Massive Tsunami: Estimated to have reached heights of 9 meters, this tsunami surged toward Crete, destroying Minoan coastal cities and ports.

Volcanic Winter: A volcanic winter followed as ash spread across the Mediterranean, reaching Anatolia, Egypt, and even Greenland (Quaternary Science Reviews).

The eruption released around 15 billion tons of magma into the atmosphere, 40 times more than the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, making it the most significant eruption in the last 10,000 years (Nature Geoscience).

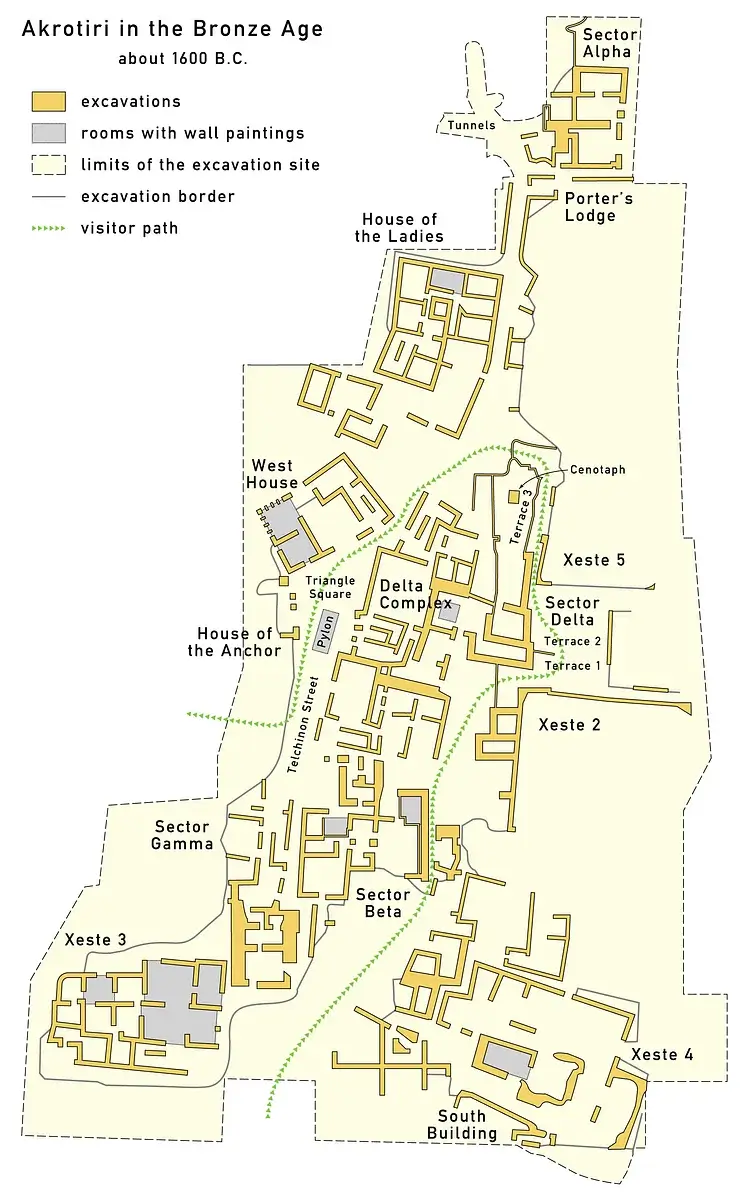

Image Source: Akrotiri during the Bronze Age

Ash in Europe and Climate Change:

The ash cloud from the eruption traveled thousands of kilometers, covering parts of Crete, Turkey, the Balkans, and even ice cores in Greenland (Hammer et al., Nature). This widespread fallout led scientists to investigate its climatic effects:

Temperature Drop: The massive injection of ash and sulfur dioxide likely caused a temporary global cooling phenomenon, disrupting weather patterns.

Agricultural Collapse: In Greece and Crete, crops may have failed due to prolonged darkness and acid rain, contributing to social instability.

Flood Myths: Some scholars believe that the eruption influenced later flood myths, including those found in Egyptian and Near Eastern texts (The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean).

Impact on the Minoan Civilization:

The Minoan civilization, centered on Crete, was heavily impacted by the eruption. Coastal settlements were devastated by the tsunami, and ash fallout disrupted agriculture. While the civilization showed resilience by rebuilding many affected sites, the aftermath of the eruption may have contributed to its eventual decline.

The Atlantis Connection:

The dramatic destruction of Santorini, combined with the advanced civilization of its inhabitants before the great catastrophe and the nearly circular geological shape of the land, has led some scholars to link Plato's myth of Atlantis with the area of Thira.