Introduction

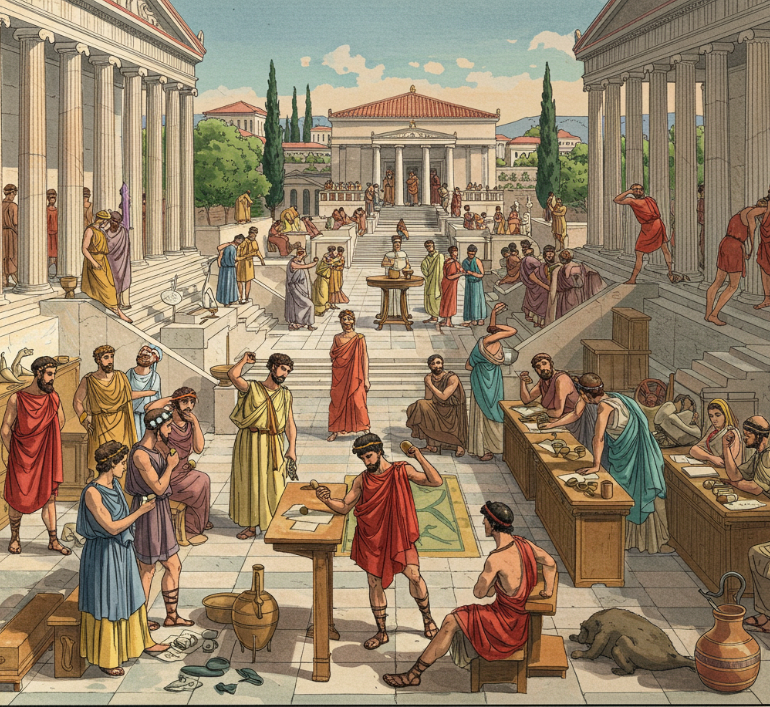

Ancient Athens is often regarded as the birthplace of democracy. Unlike modern representative democracies, Athens practiced a direct form of democracy where eligible citizens actively participated in decision-making. This system, developed in the 5th century BCE under leaders like Cleisthenes and Pericles, allowed male citizens to have a direct role in governance, shaping laws, policies, and judicial outcomes.

Foundations of Athenian Democracy

Athenian democracy was built upon three main institutions:

The Ecclesia (Assembly): The principal decision-making body where citizens debated and voted on laws, policies, and foreign affairs.

The Boule (Council of 500): A body responsible for setting the agenda for the Ecclesia and overseeing administrative functions.

The Dikasteria (People’s Court): A judicial system where large citizen juries decided legal disputes and ensured accountability of public officials.

Citizen Participation in Governance

Participation in Athenian democracy was both a right and a duty for male citizens over the age of 18. Unlike modern systems where elected representatives legislate on behalf of the people, Athenians engaged directly in legislative, executive, and judicial roles:

Legislation: The Ecclesia met approximately 40 times a year on the Pnyx hill, where thousands of citizens could propose and vote on laws.

Administration: The Boule, selected by lot, prepared legislative proposals and ensured their implementation.

Judiciary: Citizen jurors, chosen randomly, adjudicated cases without professional judges, reinforcing the democratic ideal of equal participation.

Mechanisms to Prevent Tyranny

To safeguard against corruption and tyranny, Athenians employed various checks and balances:

Ostracism: A process where citizens could vote to exile a politician for ten years if deemed a threat to democracy.

Rotation and Lot Selection: Most public offices were filled by lottery to ensure fairness and prevent power consolidation.

Public Accountability: Officials had to undergo scrutiny (dokimasia) before taking office and audits (euthynai) upon leaving office.

Limitations of Athenian Democracy

Despite its progressive nature, Athenian democracy was exclusive. Only free adult male citizens, about 10-20% of the population, could participate. Women, slaves, and metics (foreigners residing in Athens) were excluded. This limitation highlights the contrast between ancient and modern democratic ideals.

Conclusion

Athenian direct democracy was a pioneering system that empowered citizens to shape their own governance. Although it had its limitations, its principles of civic participation, legal accountability, and political equality influenced later democratic developments, including modern democratic governance. The Athenian model remains a foundational example of citizen-driven government, inspiring political thought across centuries.