In Greek mythology, the Hyperboreans were a mythical people who lived in the far northern part of the known world. Their name appears to derive from the Greek ὑπέρ Βορέᾱ, "beyond Boreas" (the God of the North Wind), although some scholars prefer a derivation from ὑπερφέρω ("to carry over").

An arctic continent on the Gerardus Mercator map of 1595. The mythical land of Hyperborea, believed to be on an island called Thule

Despite their location in an otherwise frigid part of the world, the Hyperboreans were believed to inhabit a sunny, temperate, and divinely-blessed land. In many versions of the story, they lived north of the Riphean Mountains, which shielded them from the effects of the cold North Wind. The oldest myths portray them as the favorites of Apollo, and some ancient Greek writers regarded the Hyperboreans as the mythical founders of Apollo's shrines at Delos and Delphi.

Later writers disagreed on the existence and location of the Hyperboreans, with some regarding them as purely mythological, and others connecting them to real-world peoples and places in northern Europe (e.g. Britain, Scandinavia, or Siberia). In medieval and Renaissance literature, the Hyperboreans came to signify remoteness and exoticism. Modern scholars consider the Hyperborean myth to be an amalgam of ideas from ancient utopianism, "edge of the earth" stories, the cult of Apollo, and exaggerated reports of phenomena in northern Europe (e.g. the Arctic "midnight sun").

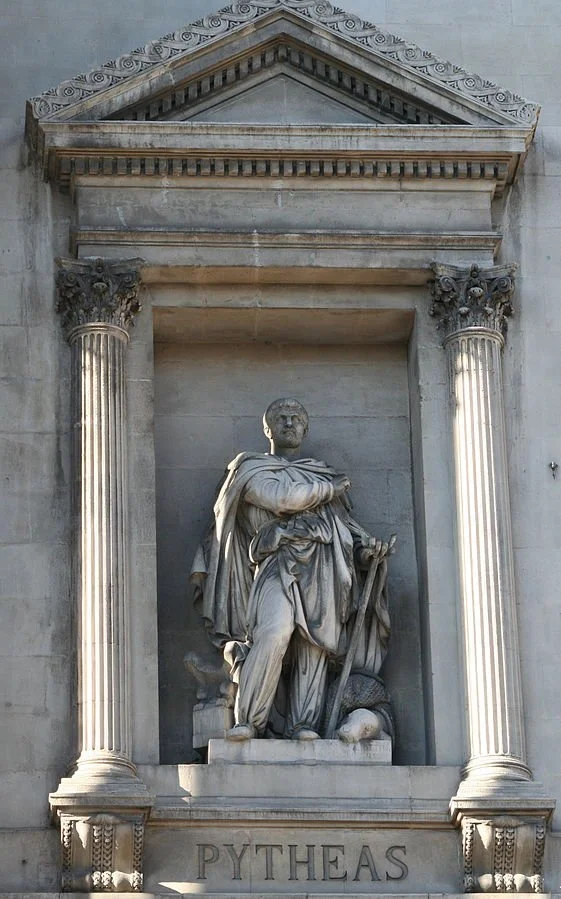

Pytheas was a Greek geographer, explorer and astronomer from the Greek colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, France). He made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe in about 325 BC, but his account of it, known widely in Antiquity, has not survived and is now known only through the writings of others.

A statue of Pytheas outside the Palais de la Bourse, Marseille

On this voyage, he circumnavigated and visited a considerable part of modern-day Great Britain and Ireland. He was the first known scientific visitor to see and describe the Arctic, polar ice, and the Celtic and Germanic tribes. He is also the first person on record to describe the midnight sun. The theoretical existence of some Northern phenomena that he described, such as a frigid zone, and temperate zones where the nights are very short in summer and the sun does not set at the summer solstice, was already known. Similarly, reports of a country of perpetual snow and darkness (the country of the Hyperboreans) had reached the Mediterranean some centuries before.

Pytheas introduced the idea of distant Thule to the geographic imagination, and his account of the tides is the earliest one known that suggests the moon as their cause.

THULE IN ANCIENT LITERATURE

Ancient Greeks had a legend of Hyperborea, a land of perpetual sun beyond the “north wind.” Hecataeus (c. 500 BC) says that the holy place of the Hyperboreans, which was built “after the pattern of the spheres,” which lay “in the regions beyond the land of the Celts” on “an island in the ocean” believed to be Thule.

In 330 B.C., Greek explorer Pytheas of Massalia, while sailing the North Atlantic, discovered what he believed to be Thule. His book About the Oceans gave an account of the journey, but it remains lost.

Cleomedes referenced Pytheas’ journey to Thule, but added no new information.

Virgil, c. 37 B.C., coined the term Ultima Thule (Georgics, 1. 30) meaning “farthest land” as a symbolic reference to denote a far-off land or an unattainable goal.

In the 1st century B.C., Greek astronomer Geminus of Rhodes claimed that the etymology of Thule came from an archaic word for the polar night phenomenon – “the place where the sun goes to rest”.

Dionysius Periegetes in his De situ habitabilis orbis also touched upon the subject, as did Martianus Capella.

Roman historian Tacitus, in his 98 A.D. book chronicling the life of his father-in-law, Agricola, describes how the Romans knew that Britain (which Agricola was commander of) was an island. He writes of a Roman ship that circumnavigated Britain, and discovered the Orkney Islands and says the ship’s crew even sighted Thule. However their orders were not to explore there, as winter was at hand.

A novel in Greek by Antonius Diogenes entitled The Wonders Beyond Thule appeared c. A.D. 150 or earlier. Gerald N. Sandy, in the introduction to his translation of Photius’ 9th-century summary of The Wonders Beyond Thule, surmises that Thule was “probably Iceland.”

Latin grammarian Gaius Julius Solinus in the 3rd century A.D., wrote in his Polyhistor that Thule was a 5 days sail from Orkney:

…Thule, which was distant from Orkney by a voyage of five days and nights, was fruitful and abundant in the lasting yield of its crops.

…Ab Orcadibus Thylen usque dierum ac noctium navigatio est; sed Thyle larga et diutina Pomona copiosa est.

In the 4th century A.D., Avienus in his Ora Maritima added that during the summer on Thule night lasted only two hours, a clear reference to the midnight sun.

The 4th century Virgilian commentator Servius also believed that Thule sat close by to the Orkney Islands:

…Thule; an island in the Ocean between the northern and western zone, beyond Britain, near the Orkneys and Ireland; in this way Thule is with the sun in Cancer, in perpetual daylight without night, it is said.

…Thule; insula est Oceani inter septemtrionalem et occidentalem plagam, ultra Britanniam, iuxta Orcades et Hiberniam; in hac Thule cum sol in Cancro est, perpetui dies sine noctibus dicuntur…

Early in the fifth century A.D., Claudian, in his poem, On the Fourth Consulship of the Emperor Honorius, Book VIII, rhapsodizes on the conquests of the emperor Theodosius I, declaring that the “Orcades [Orkney Islands] ran red with Saxon slaughter; Thule was warm with the blood of Picts; ice-bound Hibernia [Ireland] wept for the heaps of slain Scots.” This implies that Thule was Scotland. But in Against Rufinias, the Second Poem, Claudian writes of “Thule lying icebound beneath the pole-star.”

.The known world came to be viewed as bounded in the east by India and in the west by Thule, as expressed in the Consolation of Philosophy (c. A.D. 524) by Boethius.…

…For though the earth, as far as India’s shore, tremble before the laws you give, though Thule bow to your service on earth’s farthest bounds, yet if thou canst not drive away black cares, if thou canst not put to flight complaints, then is no true power thine.

In 551 A.D. Jordanes, in his Getica wrote that Thule sat under the pole-star.

Seneca the Younger wrote of a day when new lands will be discovered past Thule. This was later quoted widely in the context of Christopher Columbus’ discovery of America:

…There will come an age in the far-off years when Ocean shall unloose the bonds of things, when the whole broad earth shall be revealed, when Tethys shall disclose new worlds and Thule not be the limit of the lands.

…Venient annis saecula seris, quibus Oceanus vincula rerum laxet et ingens pateat tellus Tethysque novos detegat orbes nec sit terris ultima Thule..

Sources: arcticthule.com dictionary.com, wikipedia