The ancient Greek cuisine was characterised by simplicity: wheat, olive oil, and wine with a preference to fish. Meat was consumed rarely... This tradition in Greek diet persisted throughout the ages and changed relatively recently. With the modern technological advances meat has become much more readily available. Urbanization around the 1960s brought about similar changes such as new recipes, new ways of presentation and of course, more processed foods.

By Theo Mak Drummer, Singer, Songwriter and History geek

Byzantine cuisine, the cuisine of the Eastern Roman Empire, is distinguished mainly by the incorporation of elements of ancient Greek and Roman cuisine.

In Greece we eat various kinds of greens, healthy, delicious, boiled with added olive oil vinegar or lemon salt and pepper. A simple dish of the poor people throughout the ages and a staple of a healthy Mediterrainian diet! Their consumption has a history of 2500 years and more. We find testimonies of chorta (greens) in Theophrastus, Diocurides, Plutarch and many others.

The Byzantine dishes, whether poor or wealthy, were known for their diversity and ingenuity, from the richly flavored dishes eaten at the banquets of the aristocrats and the palace (what we now call Politiko) to the simplest dishes that became the diet of Constantinople's low and middle class residents (what we now call healthy mediterrainian diet). The modern Greek cuisine is a blend of the two and of course the foods of ancient Greece and the Roman/Byzantine empire didn't include many that are considered standard present-day Greek ingredients, like lemons, tomatoes, eggplant, and potatoes. So Greek cuisine has of course changed.

Silver spoons with Inscriptions, 500s–600s, 24 cm. long. Image courtesy of Benaki Museum, Athens

It was in medieval Constantinople that exotic spices such as ginger and nutmeg, known exclusively as medicines in ancient times, made their way into the kitchen. Crusaders passing through Constantinople returned to Europe enchanted by the scents and flavors that only seemed to add to the exoticism and splendor of that magnificent city. It was here also that these Europeans—still slurping their soup from bowls and stabbing everything else from a serving platter onto a trencher (a plate made from a flat round of bread) with their own pocket knives—had their first encounters with forks and spoons, devised to aid Byzantine nobles in protecting their long, ample sleeves from being soiled. - Getty

Byzantine cuisine represented the empire's multifaceted ethnic, racial, and cultural mosaic, though the Greek aspect was dominant at all levels dating back to the early Greek colonies that had spread around the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea since the very early ancient times. So the modern Greek cuisine is a fusion of centuries of Greek and Roman gastronomy which coexisted and interacted with all the other neighbouring cultures, including Arabs, Syrians, Jews, Armenians, Slavs, Germanics and Latins.

Other factors such as the various climatic conditions that prevailed in the Byzantine territory with its extensive geographical boundaries, the various ethnicities living within its borders, and the complex economic and social stratification played a major role in shaping Byzantine cuisine.

One thing was a definite must; all middle and upper classes made sure to have all the spices that came from the East on their shelves, such as cinnamon, walnuts, nutmeg, cumin and so on.

The presence of bread on the Greek table is timeless. Over the centuries, the Greek tradition of bread kneading has maintained its special place with many delicious pastries.

In everyday life, the main goal was the self-sufficiency of each household. Every family cultivated their basic vegetables and raised animals, usually poultry. This was happening in the provinces, in the big cities and especially in Constantinople, with as many as 1,000,000 inhabitants at its height during the Macedonian dynasty of the late 9th-early 11th centuries state care intervened, mainly through the governor (prefect) of the city. Many times the lack of bread caused problems and riots.

Dakos From Crete (of course the tomatoes are a newer addition, Europeans were introduced to tomatoes around the 16th century but it complements the paximadi bread like nothing else!)

From ancient times various authors referred to the Παξιμαδι (Paximadi) as δίπυρος άρτος (dipyros artos) meaning "double-baked bread" because simply, it was baked twice. Later on in history we find it as "paxama" and then as "paxamite" until it finally got its current name. The word comes from Paxamos, a gastronomy writer of Roman times. The Paximadi was one of the basic nutrients of ancient and medieval sailors and soldiers as it has the ability to be preserved for a long time. The production technique of the Paximadi is very simple. The bread, usually barley, is baked and when it cools, it is cut into large pieces that are put back in the oven for several hours, until they are dry.

The Greek Easter tradition of breaking the fast with a holiday feast also has its roots from the Eastern Roman Empire. The dyed eggs, the spit-roasted lamb and the lambrokoulouro or tsoureki (the sweet Easter bread) that a visitor will always see on a Greek Easter table are all coming down to us from the Greek middle ages.

Easter bread

...Easter bread Tsoureki or Lampropsomo (bright bread) or lamprokouloura (bright circular bread) is referring to the light Christians believe is given to them by Christ’s resurrection. The tradition of plaiting bread is old; it predates the arrival of the Gospel among the Greeks. While the ancient, pre-Christian Greeks also baked braided breads in order to welcome the awakening of the nature during springtime, this symbolism is one of the many religious adaptations from the old Greek religion to Christianity.

Tsoureki was traditionally prepared with an essence drawn from the seeds of Mediterranean wild cherries, called mahlepi. The bread can also be flavored with mastic, the resin from Pistachia lentiscus, variety of Chios. In more recent years, vanilla-scented tsoureki has also become popular. Tsoureki is sprinkled with nuts, usually slivered, blanched almonds, while it is often decorated on top with spring flowers, leaves, crosses and snakes made of dough....

...The Easter Egg is the other pylon of Greek Easter tradition though is associated with beliefs of particularly ancient origin.

The influence of the rituals of ancient Greece on Christianity seems to be greater than most of us realise. For the Orphics, through the deep turmoil of the night, time gave birth to the cosmic egg from which Fanis (the name of Eros in the Orphean Hymns) male and female, sprang together to begin the creation.

Orpheus Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς is a legendary musician, poet, and prophet in ancient Greek religion.

The egg was also connected with the springtime fertility rituals of many pre-Christian and peoples, like the old Cretans. In Christianity, the egg is a symbol of Resurrection, representing the emergence of Christ from His tomb to everlasting life... - Greek Easter Tsoureki & red Eggs : Ancient era and Christianity “marriage”

Ioannis Tzetzes, a 12th century Byzantine historian, thanks Alexios Pantechnes for his gifts of spices and a living partridge, adding that he preferred slaughtered animals to alive ones because he could not bear seeing blood from slaughtered animals. However, if Alexios wishes to give him meat, he should send cooked meat, or fresh meat drained of blood.

In general, the richer Byzantines had the luxury of eating fresh meat on a wider scale (of course everyone had to follow the Lent, so when we say wider we do not mean today’s levels of totally uncontrolled meat consumption. Fasting did not allow meat consumption for about half of the year).

(Tzetzes would often enjoy a plate similar to this one). The history of lentil cultivation begins very early in history, from the Neolithic era up until our modern times. One day Diogenes was eating a plate of lentils sitting on the doorstep of a random house. There was no cheaper food in Greece than lentil soup. In other words, eating lentils meant being in a state of utter misery. An envoy of the lord passed by and said to him: "Ah! Diogenes, If you learned not to be disobedient and flattered the lord a little, you would not be forced to eat lentils all the time. '' Diogenes stopped eating, looked up, into the eyes of his rich interlocutor and replied: "Oh, my dear brother! "If you learned to eat a few lentils, you would not have to constantly obey and flatter the lord."

Fresh meat was a treat for poor people like Tzetzes. As a result, he primarily relied on eggs, dairy products, legumes, cheap cuts of meat, and taricha (processed fish and meat) for protein.

The most common source of preserved meat appears to have been pork. In a densely populated city like Constantinople, preservation was the only effective way to store food for a prolonged period of time If people didn't want to sell the piglets when they were still alive.

The most popular technique for preserving meat during the Byzantine period was salting in combination with sun–drying and smoking.

Some of the many recipes that you can still taste when visiting Greece is Apaki, a Cretan delicacy, salted and smoked lean pork - HistoryOfGreekFood and also Siglino from the Mani peninsula. It is a type of salted pork with a history that dates back to ancient Greeks, recipes that were developed because of the need to preserve meat for as long as possible. The parts of the pork that are selected are usually the shoulder and the leg. They are salted, dried and smoked on fresh sage branches. After smoking, large pieces of fish are boiled in olive oil and water along with oranges. Then they are placed in containers and covered with clay (ie pork fat). In this way they are preserved for a long time.

Stuffed vegetables with rice and raisins or rice and minced meat. Tomatoes, peppers and eggplants, but also zucchini and zucchini flowers, onions is a dish that you can taste not only in Greece but in many Balkan countries and even in Austria with origins from Constantinople.

You cannot visit Greece without tasting a spanakopita (spinach pie) or a tyropita (cheese pie). Pita, (pie) with its history of course, dating from ancient Greece, where pies were part of the daily diet. The dough contained milk, olive oil, fat cheese, eggs, honey, herbs, spices and/or nuts. Characteristic was a kind of pie with honey, cheese and oil and the "mitlotos" - a pie with honey and garlic - which was very popular. Another kind of pie that the ancient Greeks ate especially in the morning was based on flour and wine. Another typical pie was the "maza" (mass) with barley, rye, oat or millet flour and various legumes. In the symposiums of the ancient Athenians, desserts included fresh and dried fruits, savory almonds, cheese and ended with savory and sweet pies.

Spanakopita (spinach pie)

During the Middle Ages, we know that pies were as popular as they are now in modern times and in fasting, pies were very common i.e spanakopita (spinach pie) or chortopita (greens pie).

Today, cheese pies, meat pies, spinach pies or onion pies and so on are common and very popular as a snack, a starter or even as a main dish in all parts of Greece, as well as skaltsounia, puff pastries and tarts are nothing but variations of the ancient Greek pie which in its original form was simple and was baked on hot stones.

Skaltsounia or Kalitsounia from Crete sweet pastries with cheese filling

To put it simple; Many of the dishes that you will taste when visiting Greece are a journey of centuries and centuries of history! :-)

And of course you cannot have a nice meal without a glass of good wine. The earliest evidence of Greek wine dates back to 6,500 years ago. Wine, Vin, Wein, Vino comes from the ancient greek word for wine οἶνος. Which was pronounced kind of like winos (with a soft W).

The ancient Greeks drank wine by mixing it with water, usually in a ratio of 1: 3 (one part wine to three parts water). The modern greek word for wine is "krasi". Τhe word originates from the Middle Ages, (mediated by the types krasin <krasion), from the word krasis = mixing, as they used to say ᾽κράσις οίνου᾽, (mix the wine). In Byzantium, large areas of land belonged to the Church and the monks took on the cultivation of the vines as well as the production of wine. In fact, the practice of mixing wine with water must have been abandoned during this period.

For all etymologies, and the funny maxim of Eyvoulos below, kudos to my Ancient Greek teacher, Ελένη Ωρείθυια Κουλιζάκη

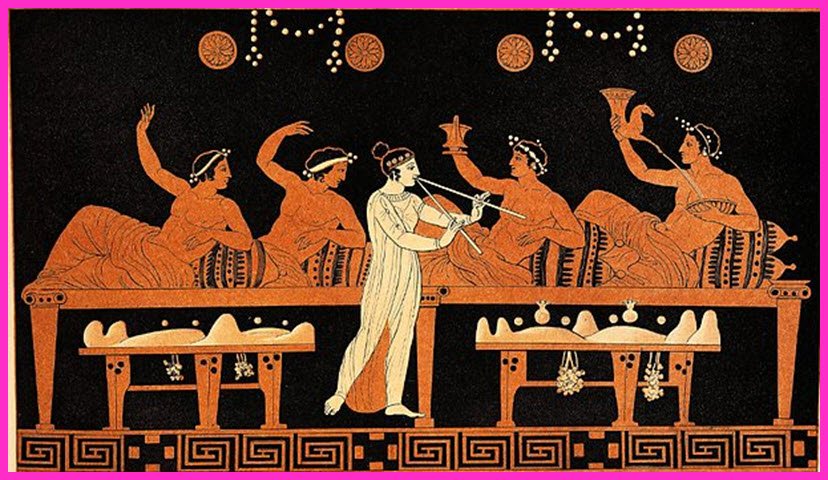

Symposiums... A very MEANINGFUL party!!! Tables were cleared and set up again with dried fruits, nuts, pies, cheeses and sweets as tid bits to accompany the guests’ drinking and philosophical conversations. The wine flowed abundantly, watered down this time at a ratio that was defined by the Toastmaster, who was randomly elected. Dancers, musicians and acrobats entertained the attendees while they toasted, sang and conversed up to the early morning hours.

‘’...Three glasses of watery wine are enough: One for good health, which I empty first, the second for love and pleasure I drink it, the third one to sleep. When the third cup is empty, the wise go home. The fourth is an exaggeration, and given to violence, the fifth in anger, the sixth in rage, the seventh in the blurred look, the eighth is of the policeman, and the ninth in madness, rage, breaks and destruction devoted...’’

(Eyvoulos, 175 B.C.)

Drinking wine that was not mixed with water ("unbridled wine") was considered barbaric. The consumption of wine with honey as well as the use of spices were also widespread. Adding absinthe to wine was also a well-known method (attributed to Hippocrates and referred to as "Hippocratic Wine") as was the addition of resin. The drink of Retsina that you can still find in Greece today.

In 968, Liutprand was sent to Constantinople to arrange a marriage between the daughter of the late Emperor Romanos II and the future Holy Roman Emperor Otto II. According to Liutprand, he was treated very rudely and in an undignified manner by the court of Nikephoros II, being served goat stuffed with onion and served in fish sauce and "undrinkable" wine mixed with resin, pitch and gypsum—very offensive to his Germanic tastes. Retsina

And of course the drinks of Tsipouro and the famous Ouzo. Tsipouro is a strong distilled spirit that contains 40–45 percent alcohol by volume and is made from either the wine press residue or the wine after the grapes and juice have been separated. It is typically not aged in barrels, though barrel-aged versions do exist. The anise flavoured Tsipouro is what we call Ouzo!

Cheers or lets better say ΕΥΟΙ ΕΥΑΝ (to good health, well being, in ancient Greek)… ΕVΙVΑ (which is still used today and its a shorter version of EYOI EYAN), ΕΙΣ ΥΓΙΕΙΑΝ (To Health), ΓΕΙΑ ΜΑΣ (To our Health)!

Cheers, to our health a drinking wish spanning centuries and centuries!