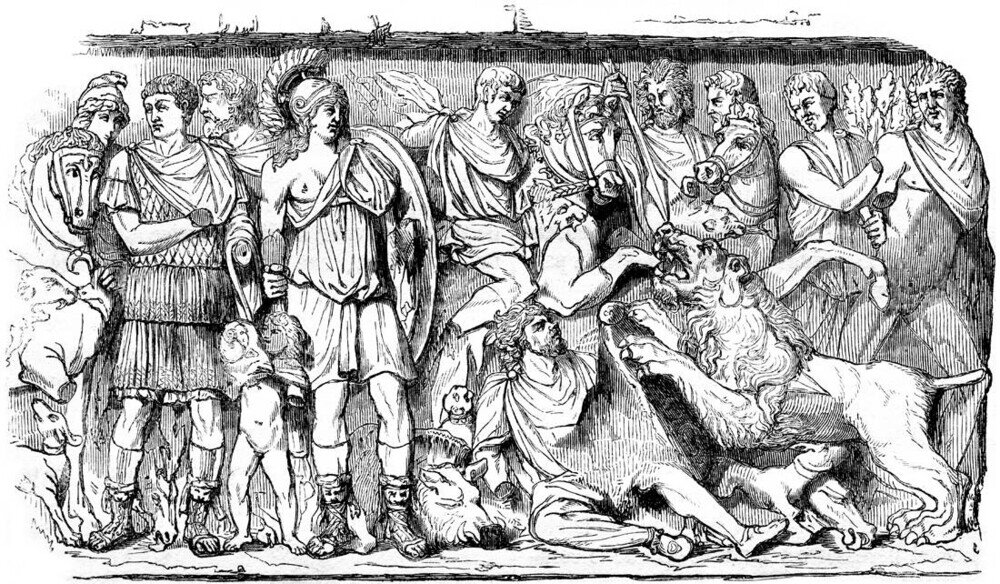

We know Gauls today from Asterix and Obelix and the adventures of Rene Gossini and Albert Uterzo, but to our ancient ancestors, they were a serious threat that arose to plunder, destroy and possibly colonize.

Taking advantage of the complete weakening of Greece by the fierce battles between the Hellenistic states, the Gauls set out from Pannonia in the southern Balkans in the late 3rd century BC with at least destructive intentions.

The ruthless Brennus II (not to be confused with Brennus, who conquered Rome in the 4th century BC) led thousands of Gaulish warriors into Macedonia and caused enormous damage there.

Sosthenes opposed them in this first phase of their invasion, but they buckled and returned even stronger, advancing as far as Thessaly, for their goal was the wealth of the Oracle of Delphi. Against them, they would now meet the organized resistance of the Greeks, warriors from Athens, Megara, Fokida, Aetolia, and Boeotia, who, led by the Athenian general Kallippos, and were to witness the second Thermopylae of Greece, 201 years after the first and most glorious.

The prelude of the invasion

The third decade of the 3rd century BC found the Greek states exhausted by the quarrels of Alexander the Great's successors. In 281 B.C. the king of Thrace, Lysimachus, once a young man of the Macedonian general, is killed and leaves his kingdom to the desires of his enemies.

The Gauls of Pannonia decide to undertake a campaign to the south of the Balkans, as the situation there is particularly favorable. The troubled situation in the predominantly Greek area and the struggles of the descendants of Alexander the Great had brought the city-states to their knees and called for broader alliances. Confederations now emerged, Aetolia in 290 BC and Achaia in 280 BC, seeking to increase their self-government and independence.

At the same time, the Celts were by no means unknown to the Greeks. The Celts of the Adriatic had been repulsed by Alexander the Great, which forced them to swear eternal friendship, as the geographer Strabo and the historian Arrian tell us.

Celtic mercenaries also served for more than a century in the city-states of Greater Greece, and a band of them had even been sent by Dionysius the Elder (tyrant of Syracuse) in 369 B.C. to assist the Lacedaemonians in their conflict with the Boeotians, as Diodorus of Sicily testifies to us.

But the old friends were eventually to turn into a great enemy, who found a suitable ground in Macedonia, weakened by the battles of Lysimachus and Seleucus.

Lysimachus was killed, but Seleucus could not rejoice in his victory, for he was assassinated by Ptolemy Keraunus who was anointed king of Thrace and aimed for Macedonia after securing the friendship of Pyrrhus, king of Epirus.

And he succeeded, defeating Antigonus II Gonatas, son of Demetrius the Besieger, and was crowned king in Macedonia. With Pyrrhus in Italy and Macedonia brought to its knees by war, northern Greece seemed an easy target for the Gauls. They gathered about 85,000 men and started a war.

Their army was divided into three parts: one division - under Kerethrios - attacked Thrace, a second - under Brennus - invaded Paeonia, and the third - under Belgius - attacked Macedonia and Illyria. Ptolemy Keraunus suffered a crushing defeat on his elephant, underestimating the scale of the threat, and fell into the hands of the Gauls, who beheaded him and nailed his skull to a spear, which they distributed throughout Macedonia as a trophy.

Without an opponent anymore, the Gauls plundered the defenseless Macedonian countryside with terrible fury, as it has come down to us, letting whole tracts of the country fall desolate without attacking towns, as they did not know the art of siege. The defense of Macedonia was undertaken by the aristocrat Sosthenes, who was anointed commander of his own accord and succeeded in driving the foreign race from the Macedonian land.

The Gauls, who at this time were bent on robbery and plunder, withdrew into their own country, but they did not remain long inactive.

The Gauls roar for the second time

Brennus never stopped pushing for a second attempt against Greece, for he had not only plunder in mind. He dreamed of a colony in Greece and had a way to achieve it. At least he thought he did. He went so far as to show his wealthy men the malnourished Greek captives in his possession, the smallest and most suffering of them, and said that they were no great adversary for the ruthless Gauls. And he succeeded in convincing them that Greece had incredible riches in its coffers and gold at Delphi. With Akichorios at his side and an army of 200,000 men, he was ready to campaign again in 279 BC, this time in southern Greece. He had with him women, children, and the elderly, for the goal now was to establish a permanent base. Both the traveler and geographer Pausanias and the Roman historian Justin gave detailed accounts of this second descent of the Gauls.

The Celtic hordes of Brennus II again received the first blow from Sosthenes, but managed to overcome his defensive line and pour into the land of Thessaly, suffering heavy losses. They forced the Greeks to take up arms. Pausanias tells us in "Hellas Periigisis":

"Greek valor was lost in a few moments, but the power of fear made the Greeks realize that they had to fight. They knew that this fight was for their freedom, as when they faced the Persians. The events that had taken place in Macedonia, Thrace, and Paeonia were still fresh in their memories, while in Thessaly new bloodshed was now taking place. "Every man as an individual and every city as a whole realized that the Greeks must either face the circumstances or perish."

It was time for the second Thermopylae of Hellenism against a foreign enemy.

The glorious Thermopylae

The narrow gate, which was a passage to the south of Greece, was once more chosen as the ideal point of fortification for the united Greek army since the ambush of the Greeks at Sperchios was a failure.

Brennus, after his adventures with Sosthenes, had 152,000 hoplites and 24,400 horsemen in his ranks (the horsemen were three times as many, as each of them was accompanied by two cavalry slaves), and found the Athenian general Kallippos and his 26,000 brave men facing him. But also several ships which had already lined up in the strait.

Most of them were Boeotians (10,000 hoplites and 500 horsemen), while another 7,000 hoplites were Aetolians. The Phocians sent 3,000 hoplites and 500 horsemen, the Lokros 700 soldiers and the Megarians another 400. The Macedonians sent 500 men and another 500 came from Antioch of Asia Minor. The rest were Athenians and there were the Triremes too, as Pausanias estimates their number. The Spartans and the other Peloponnesians sent no help, feeling safe thanks to the fortifications at the Isthmus of Corinth.

The battle was fought in a marsh in the straits of Thermopylae, where the Greeks dealt a significant blow to the superior Gaul army. The Greek army waited in silence for the Gauls, and as soon as they appeared the infantry withdrew, leaving the light-armed to shoot with spears, arrows, and stones, as the cavalry being put out of action by the nature of the ground. Arrows were also fired by the Athenian triremes, which were dragged to the shore with a great effort.

Brennos buckled after the defeat, and seven days later, by a tactical maneuver, sent part of his expeditionary corps (40,000 hoplites and 800 cavalrymen) eastward, into Aetolia, to force the Aetolians to abandon the straits and protect their fortresses.

The Gauls completely wiped Kallion (modern Klausi near Karpenisi), an important city on the border between Evrytania and Aetolia and committed unspeakable atrocities. It is reported that they slaughtered all the inhabitants and performed cannibalistic acts, as Pausanias reveals in the tenth book (Fokika) of "Hellados Perigisis":

"The most outrageous and horrible acts I have ever heard of occurred. The Gauls slaughtered all the men of the tribe, drank the blood and ate the flesh of the slaughtered infants. As soon as the city fell, their proud women committed suicide rather than fall alive into the hands of the enemy. The Gauls did not seem to be discouraged by this: they sodomized the dying women, even those who were already dead. "

The Aetolians, learning the tragic news, actually withdrew from Thermopylae to drive the terrible threat from their land. The new confrontation took place in what is now Kokkalia, a place that owes its name to the scattered and shattered bones that the locals found on the ground for years as timeless signs of the terrible battle that had taken place.

The guerrilla warfare of the Aetolians and the tenacity of revenge succeeded: of the 40,000 Gauls who had been dropped from Thermopylae, less than half returned to the straits.

The operation against the sanctuary of Delphi

Traitors like Efialtes, however, were never absent from Greek history, and just as at the first glorious Thermopylae, Greek deserters (Heraclionites and Ainians) pointed Brennus to the bypass, the same hidden path Persis Hydarnis followed to surrounded king Leonidas.

Brennus took 40,000 men and surrounded the Greeks, forcing them to retreat from the strategic strait. The Greek armies actually retreated, each to their own place, leaving southern Greece to the bloodthirsty Celts. Brennus left Akichorios and set off for Delphi, where he intended to plunder the treasures of the temple of Apollo.

The second conflict was to take place at Delphi, where the Delphians tried to repel the rock climbing Gauls with everything they had, stones, arrows and spears. On their side, as Pausanias brilliantly relates, were the gods, that is, the weather elements, for the heavy storm made the ascent of the Gauls impossible.

The Greek army overtook the Celts the next day and surrounded them when the Phocians descended Parnassus and attacked Brennus from the rear. The Gauls fought valiantly, reports Pausanias, but Brennos was wounded and they were forced to retreat. Panic-stricken, they now turned on each other, Pausanias says, and the Phocians informed the other Greeks of the general panic that prevailed in the enemy's ranks.

About 6,000 Celts died in the battle and another 10,000 in the confusion and the continually falling rocks of the landslides. Brennus allegedly committed suicide, although Pausanias, Justin, and Diodorus disagree on that. It is possible, however, that he ended his life, as he was suffering from severe wounds. The Celts used to commit suicide when they could no longer fight, as they considered slow martyrdom an insult and disgrace.

When the Athenians learned of the positive news, they left their city again, joined forces with the Boeotians, and began the pursuit of the Gauls, who were trapped in a certain place, with Aetolians, Thessalians, and Malians on the other side.

The final massacre of the invaders was to take place at Sperchios, and most ancient historians agree that no one escaped. More likely, however, many survived and dispersed to the north and Asia Minor where they actually established a colony. The barbarian threat was over, but the Greeks, despite the dire situation and the animosities between them, banded together and triumphed with enviable determination.

The Greek spirit, despite its decline and fall, despite the civil conflicts, confronted with an extremely strong and superior enemy and prevailed. And, as many historians claim, this resistance of the weakened Greeks against the powerful Gauls is perhaps even greater than the resistance against the Persians, because Greece was then flourishing and prospering.