The Swastika is one of the most common and enigmatic symbols in human history. It has been found among hundreds of the cultures around the world. It has been carved onto 30,000 year old mammoth tusks, it has been found on Neolithic Serbian tablets, its use has been noted in West Africa, the Indian sub-continent, Scandinavian and Germanic cultures and it was even employed during the period of Roman Christianity. However in all of these cultures, the swastika possessed a different meaning, whether it was another symbol for \ in Hinduism or, in some Native American cultures, it was a representation of the four winds.

Author: Casper Jackson

Cardiff University, Ancient History, Graduate Student

Some writers have been ascribed as being linked to deities such as the god Baal and Agni (Wilson 1894: 771-772). Now with the swastika appearing almost everywhere, it is hardly surprising that we find it in Ancient Greece. The Swastika is not exactly new to the Aegean. From excavations at the House of Tiles on Lemnos, we can find swastikas on some of the seals that were excavated there and there is evidence of it being found in the Minoan period. The most notable evidence of the use of the swastika is at Hisarlik most commonly known as the site of the city of Troy, where swastikas were found by Schliemann decorated upon ‘spindle whorls’ (Schliemann 1881: 350; D’Alviella 1894: 60). While it appears somewhat in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, we find a large amount in Archaic Greece.

Now the Archaic period is an exciting time in Greek History, the ‘Dark Ages’ are over and a ‘structural revolution’ (Snodgrass 1980:13) is occurring. The polis starts to develop, democracy is established in Attica and Greek colonies continue to grow. This is the time of Solon, Lycurgus, Draco, Peristatos and Thrasybulus, and it is a time where great wars were fought such as the First Messenian War and the Greco-Persian War. Thought is changing as philosophy rises in the 6th century and literature develops as we see the emergence of Homer and Hesiod’s works. We see art develop from the Geometric style to the Black-Figure and Red-Figure style. More importantly we see the development of a Greek Identity that is quite unique.

With all this change and development, one often overlooks certain features. In this case it is the use of the swastika in material culture of this period and this is what this paper will be addressing. What will be specifically discussed is the meaning of the swastika in Archaic Greece, focussing particularly on the Geometric and Orientalising periods as it is in these periods where we find an abundance of this symbol.

What this paper will be attempting to discover is what the swastika symbolises or represents in the Geometric and Orientalising eras. Is it a symbol of auspiciousness? Is it just another form of decoration? Is it a symbol of life? Or is it more than that? What this paper will not do is step outside the confines of Greece. There will be no intentional cross-cultural comparison of the use of the swastika. The reasoning behind this is simply because of the fact that swastika appears all around the world. If one does perform cross-cultural comparison then that implies that the swastika has an almost uniform meaning, but also it would lead one on a ‘wild goose chase’ of attempting to trace the swastika throughout the world and to see what extent external cultural influences had on Ancient Greece.

Etymology:

“I do not like the use of the word svastika outside of India. It is a word of Indian origin and has its history and definite meaning in India. * * * The occurrence of such crosses in different parts of the world may or may not point to a common origin, but if they are once called Svastika the vulgus profanum will at once jump to the conclusion that they all come from India, and it will take some time to weed out such prejudice.” (Muller in Schliemann 1881: 346)

I would tend to agree with Muller’s words regarding the etymology of the swastika. This word implies its own meaning, and as we see above, an issue that Schliemann addressed

(Muller in Schliemann 1881: 346). The word swastika comes from the Sanskrit word svastika (Wilson 1894: 769-771). It is composed of su- meaning "good, well" and asti "to be". Suasti thus means "well-being." (Wilson 1894: 769-771; Dumoutier 1885: 329). The suffix -ka, means "soul", so suastika can be translated as "that which is associated with well-being" (Wilson 1894: 769-771). Muller disagreed with the application of this word to the symbol, simply because of the fact that it may compel the reader or the public to consider to be of Indian origin (Muller in Schliemann 1881: 346).

Before the adoption of this particular name and certainly in earlier academic studies, various names had been ascribed to this symbol, the most ‘popular’ being the Fylfot and Gammadion. In the same as the swastika implies a meaning, both of these terms imply meanings in In the case of the Fylfot, it was the common name given to the Swastika in regard to the Anglo- Saxon period and it was maintained to have been derived from the Anglo-Saxon fower fot, meaning four-footed, or many-footed. (Greg 1885: 298 in D’Alviella 1894: 39) Similarly it was thought that the word is Scandinavian and that the roots of the word were found in the Old Nordic word: foil (Waring 1874: 10) (This implies that there is some significance in the multitude of the ‘points’ of the Swastika, even the mentioning of feet also implies that there is significance. Equally the term Gammadion suggests an unclear meaning. First of all it insinuates that the swastika is of Greek origin, which it certainly is not. Secondly, it implies that “Gamma” is significant and thus leads to question the symbolic significance of the letter “G” which unless there is a clear understanding of the symbolism of this letter, renders it problematic.

1.However for the sake of simplicity and familiarity the term “swastika” will be used as opposed to any other term.

Key information

Examples of the swastika in material culture can be found in most parts of Greece. We can find numerous examples in Attica, Boeotia, the Argives and other parts of mainland Greece. We also have examples from the Aegean, in some cases the Cyclades, ranging from Naxos, Thasos and Milos. The most common objects the swastika is found on is pottery, both in the Geometric and Orientalising periods. For example it can be seen on kraters, pyxides and amphorae. It is quite uncommon for it to be found on anything else apart from pottery, though it can be found on coins dating to around the Orientalising period. It is in the Geometric period, where we find quite large use of the swastika, and it is in the Geometric period that we see significant development of the swastika. It is in the final years of the Orientalising period that we see its decline. A point worth mentioning is that it is common for the swastika to be found among circles and birds, a fact that Anna Roes pointed out in her 1933 book “Greek Geometric Art: It’s Symbolism and its Origin” (Roes 1933: 13-17).

Animals

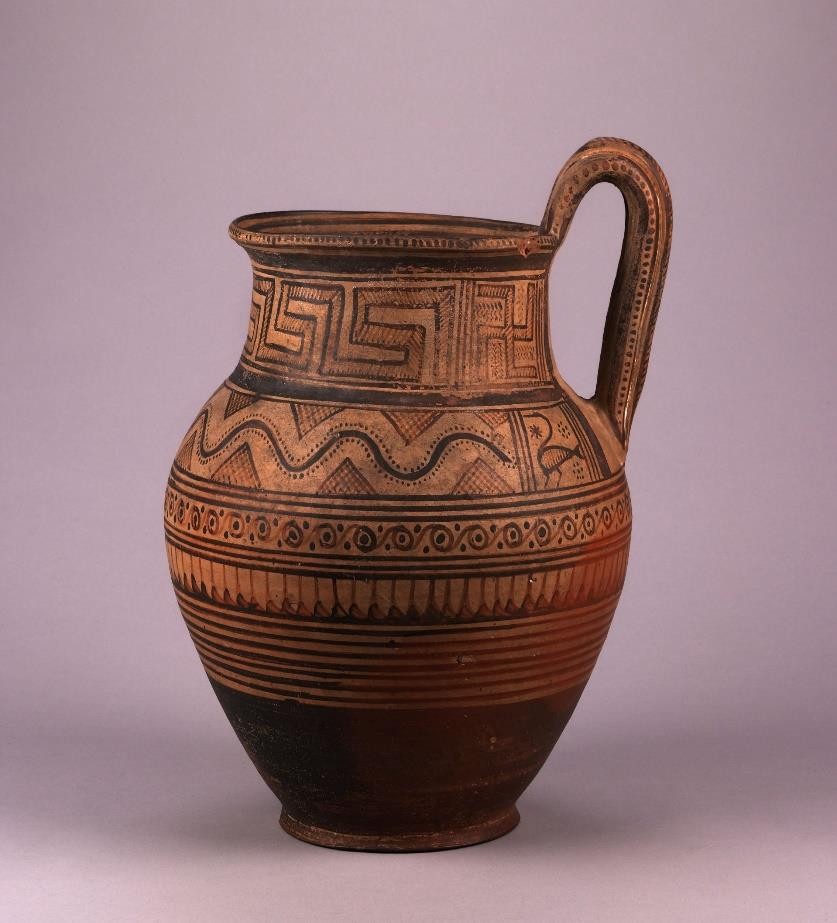

In this example (fig.1), we see the swastika very much being associated with life. While not much is known about this pitcher one could theorise that it was used for carrying water, given that it does not appear to have the hallmarks of a wine-vessel. Here we see various motifs being employed such as tangential circles, depictions of serpents and birds and other typical geometric designs. In this case the tangential circles might represent water ebbing or possibly waves, the bird might be a crane or a heron, the serpent maybe a water snake but it might also be a representation of a river meandering as well. Perhaps the pitcher was given as a gift to new families to symbolise fertility or good health, incorporating the concept of good luck and life into one in a seamless fashion. The swastika in this case might be simply another piece of decoration to emphasise the purpose of this pitcher, rather than having a specific isolated meaning.

Fig.1: Late Geometric 1b pitcher. Found in Attica. Source: British Museum.

Here once again we see the swastika among depictions of life. In this case, several swastikas flank two lions in the middle of a hunt (fig.2). Here, I feel the swastikas’ purpose are not only to symbolically represent life, but also to emphasise the danger and the value of these lions. Lions are certainly dangerous creatures, and can easily kill a man, especially in the days where technology was not as lethal as it is now. They were probably seen as a predator equal to mankind. But also one must remember that in Ancient Greece Lions symbolized power and wealth, largely because they were featured quite often in many ancient Greek myths, most famously in the tale of Heracles and the Nemean Lion.

Fig.2: Milesian (MWG) Oinochoe. Author: Katie R 2014.

While horse handled pyxides are very fascinating objects in themselves, the examples which possess swastikas are especially interesting. The swastikas adorning this pyxis (fig.3), are found in panels on the side of the pyxis, but while it might be quite hard to see, also in front and behind of the two horses on the lid. Even in Archaic Greece, horses were are very important and were highly valued for several reasons. The main reason being that horses were indicator of wealth. With good pasture so expensive, horses remained a symbol of wealth throughout all of Greek history. They were used mainly for the “essentially upper- class pastimes of hunting and racing in peacetime and for cavalry service during wartime.” Overall it appears that the swastika here is supposed to emphasise not only life but the value of horses and also the influence the owner might have.

Fig.3: Fig. 3 Late Geometric Pyxis. Museum of Ancient Agora of Athens. Author: Heidi Kontkanen 2012.

People

Like animals, the swastika can also be found among scenes where people are the dominant subject.

In this example, involving the use of swastikas, could be said to be quite unusual. The detail of the krater (fig.4) depicts a shipwreck and several men drowning, one specifically drowning and being eaten by a large fish (perhaps a shark). The swastikas are used many times in the scene, such as being placed where oarsmen might sit, and flanking the decoration of fish and men. What is interesting here is that the swastika is being used in relation to death in reality. In some manner, life is still being depicted here but it is focussing on the death, which in its way is a part life and possibly was considered as such. However we could also take into account the scene of the sailor’s body being eaten that the swastika accompanying this image, is supposed to indicate a ‘circle of life’ concept. The fish is being provided sustenance thus continuing its life. The swastika’s adorning the oarsmen’s positions might be an indicator of fate likewise the other swastikas may certainly be symbolic representations of this as well1.

Fig.4: Late Geometric Ischian Krater. Source: John Boardman 1998.

An interesting note that could be made is that not all the swastika’s share the same design, the one by the ‘feeding’ scene has dots on the inner parts of the swastika while another has dots on the tips. Perhaps there is more importance being placed on these. Overall this piece is once again an example of where the swastika is being associated with life.

Here we see another example of the swastika being used to represent life and death. On one side, and in the top panel, the swastika is seen in between three women, two of them placed above two separate dot rosettes with various motifs below that (fig.5). Would it not be a reasonable assumption to see the swastikas as an emphasis of the significance of women and their fertility? In the next panel, we see the swastika flanking two dogs, another example of how the swastika is never too far away from ‘living things’. However when we get to the next panel, the meaning is not that easily obtained. What is depicted is quite difficult to say, it might be a chariot race or it could easily be a scene of battle. If it is the latter then one could assume that it is another example of where the swastika is used as a symbol of death or fate. However if it is a depiction of the former, then it might be possible that the swastika is being used as a symbol of auspiciousness.

Fig.5: Proto-Attic Amphora. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Author: Ad Meskens 2009.

This idea was suggested in a discussion with Jannett Morgan and Ruth Westgate.

Finally, with regard to this Amphora, we see a man riding a horse, and among the typical solar symbols, we can see two reasonably large swastikas above and below the rider (fig.6). Certainly one can presume that the swastikas here are supposed to emphasise some quality or represent something simply because of the size and positioning compared to all the other astronomical/solar symbols. It almost looks like that the swastikas here are both for the rider and the horse, positioning being respective to each. Perhaps it is to emphasise the luck and wealth of the rider in question, given the value of horses in Archaic Greece.

Fig.6: Late Wild Goat style plate from Rhodes. Source: John Boardman 1998.

Mythological Creatures

In the Orientalising period, we see a broadened use of the swastika. No longer is it only used in regard to ‘real’ life, we now see the beginning of the association of the swastika with mythological creatures. To begin with, we can see the swastika being used as part of the overall design on artefacts where the main subject is a gryphon. An important thing to note is the significance of gryphons in Ancient Greek culture. An account ascribed to Aeschylus points to gryphons being associated with Zeus (“Beware of the sharp-beaked hounds of Zeus that do not bark”) (Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound, 802 in Weir Smyth 1926). If this sentiment was shared among the majority of Greeks before Aeschylus’ time then, it appears that one would certainly wish to not anger Zeus. It appears thus that the swastika is very much entangled in this. For our first example one can point to this Samian WG panel from a krater found in Samos (fig.7). The usual symbols we find the swastika in partnership with the swastika are a present such as the bird (in this, the bird might be a goose) and two circles or wheels with four points erupting from the centre. The gryphon, in this piece, is surrounded by solar or astronomical symbols and also surrounded by four swastikas. What should be noted is that all of this on a krater, which would further imply that it was used at symposiums. Perhaps the design of the krater was to impress guests by showing that the owner is ensuring that Zeus is honoured through the krater’s use, thus earning him the god’s blessing. This would mean that the swastika’s use here is to emphasise the apotropaic qualities of this item, or to generally display luck here.

Fig.7: Samian Wild Goat Krater Panel. Sourcer: John Boardman 1998

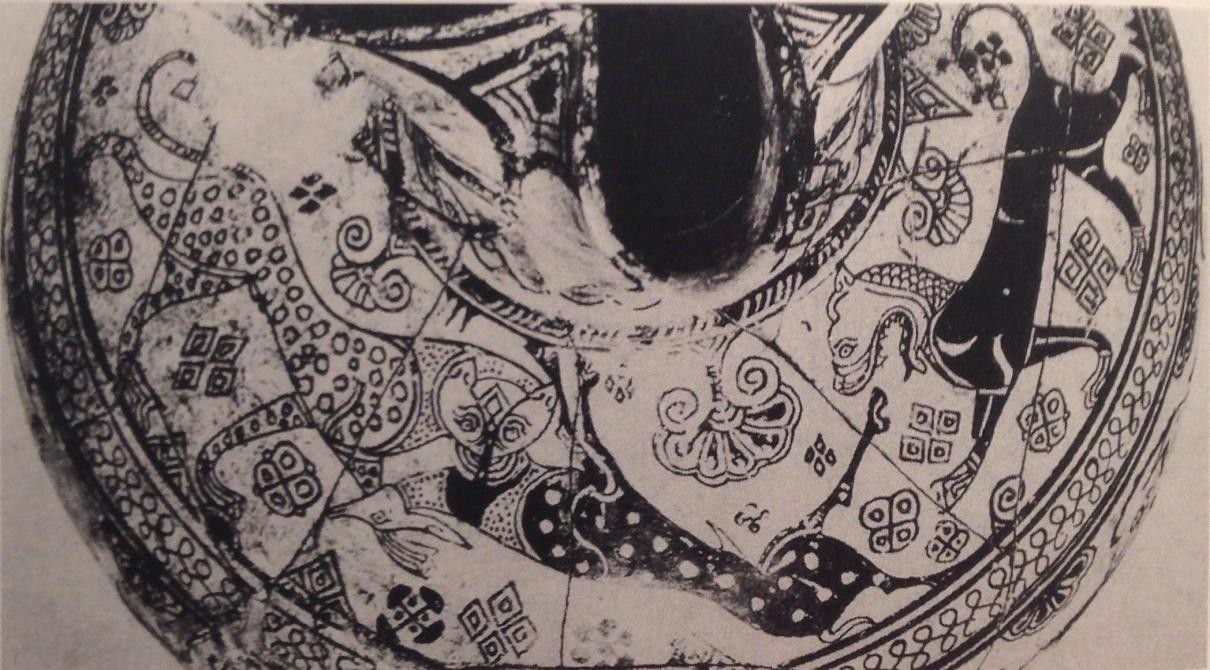

Another example is this Milesian Oinochoe, which shares similar motifs, and might very well share the same meaning. On the first one (fig 8), in particular on the top panel we see a gryphon, surrounded by swastikas as well as a goose the left of it. On the panels below we can also see numerous wild goats which also have swastikas surrounding them. One can notice that the majority of the swastikas are positioned below the goats and likewise with the gryphon. The design appears to be too well thought for it to be just a mere coincidence, and it might be that the potter’s desired effect was to show that gryphons did exist, just like the wild goats, and the swastika is present to emphasise the ‘reality’ of this belief.

Fig.8: Milesian Wild Goat Oinochoe. Source: Louvre Museum. Found in Dimitris Paleothodoros 2007, "Wild Goat Style Pottery".

Gryphons are not the only mythological creature that one encounters. On this plate (fig.9) we can see a portrayal of a Gorgon or, as John Boardman puts it, a Gorgon-headed goddess (Boardman 1998: 156). As we have seen in the myth of Perseus, the Gorgon was a fearsome monster that killed many men that encountered it. If one looks closely, it appears that the Gorgon, with a swastika to the right, has its hands grasped around the necks of these geese (one even has a swastika painted in the centre of it), it looks like she is either in the process of strangling them or is holding ones that are already dead. In Ancient Greece, the face of a Gorgon (Gorgoneion) often was used as an apotropaic symbol and placed, for example, on doors, walls and floors (Garber 2003: 2). Thus the swastikas here appear to emphasise the danger of the Gorgon, and its ability to take life away from a person, and given the gorgon’s use as an apotropaic symbol, it is likely that the swastika is also being used as a good luck symbol.

Fig.9: Gorgon/Gorgon-Headed Goddess plate from Rhodes. British Museum. Author: Marie- Lan Nguyen 2007.

Finally in terms of mythological animals, one can point to the use of the swastika with the Sphinx. On this plate, presumably from Rhodes (fig.10), we see depictions of the Sphinx, surrounded by astronomical symbols such as dot-rosettes and uni-lateral crosses. Here we can see two swastikas, both painted in different styles, in front of where the sphinx is facing. One is placed right next to her face and the other in front of her front legs. Once again we see the swastika being associated with mythological/supernatural life. In Ancient Greece, the Sphinx was seen as creature of death and bad luck (www1). The name of the creature itself even points to the ‘negative’ connotations of this creature (The word sphinx comes from the Greek Σφίγξ, which itself is supposedly from the verb σφίγγω (sphíngō), meaning "to squeeze [www1]). To be honest, it is reasonably difficult to say what the swastika is supposed to represent here. Obviously one can come back to this recurring theme of life, or in this case mythological life. It might be that it is linked to the conception that the sphinx is a bringer of death. However as said before, the sphinx is also associated with bad luck. It might be that the swastika here is a symbolic representation of luck, possibly bad luck.

Fig.10: Late Wild Goat Style, possibly Rhodian, plate from Tocra featuring a Sphinx design. Source: John Boardman 1998.

Mythology

The swastika appears very often on pieces where the subject or subjects are from Greek mythology, some are scenes from myths and some include characters from famous myths without any obvious context.

In these two examples of narrative art, we can see scenes from the Iliad. One of them appears to be displaying the funeral of Patroclus from the Iliad and the swastika (fig.11), three of them placed above a funeral pyre2. While they might be simply representative of stars, given the context these swastikas are being placed in, it seems very likely that they are more so emphasising the concept of death or fate.

Fig.11: Hirschfeld Krater. Scene depicting ekphora and a chariot race. Funeral of Patroclus? Source: John Boardman 1998.

In other the piece (fig.12) we are shown another scene from the Iliad, in particular the duel between Menelaus and Hector who are fighting over the body of Euphorbus. On this plate a large swastika is placed between the body of Euphorbus and Hector. A smaller swastika has been painted to the right or behind Hector. In this case, the swastika’s here can be viewed as being linked to death. The first signifier of this is possibly the swastika that hovers near Euphorbus, but also the size of this particular swastika may be an indicator. Given that this swastika is larger than the other one, it might be that the potter wished to emphasise that this death just occurred. In regards to the other swastika, it might be that it is supposed to be linked with the fate of Hector. It might be that the swastika’s here are also signifiers of the casualties of the Trojan War. There is no swastika behind or especially close to Menelaus, and this might very well be because of his death occurring after the end of the Trojan War.

Fig.12: Rhodian Middle Wild Goat style plate depicting Menelaus and Hector fighting over the body of Euphorbus. Author: Jastrow 2006.

Another example of Homer’s work having links with the swastika is this Attic Amphora, where the top panel shows the blinding of Polyphemus by Odysseus (fig. 13). In this example the swastika is placed between Polyphemus and Odysseus.

Fig.13: Proto-Attic Amphora depicting the blinding of Polyphemus by Odysseus and his soldiers. Found in Archaelogical Museum of Eleusis. Author: Napoleon Vier 2003.

2 Possibly a Homeric reference here given the use of the number three

Here the swastika is not so much of a symbol of life or even death but rather a symbol of fate, largely because Polyphemus does not die from his blinding nor is he killed when Odysseus and his men escape.

On this Melian amphora, it could be said that the swastika looks very much like a symbol of auspiciousness given the context of the scene. In this piece we see Heracles (fig.14), another man and two women. John Boardman states that it is a scene depicting Heracles and his wife, although it is not clear which of Heracles’ wives it is (Boardman 1998: 131). This scene of a couple certainly could have many connotations, it could be representative of life but it might be that it is emphasising the importance of marriage in Greek society. By this I mean, that if great heroes like Heracles are married then this might convince a Greek man or woman on the importance of marriage. One might also wish to consider that the swastikas here are not only facing one direction. We see on one side the swastikas facing to the right and on the other side we see the swastika facing the opposite direction. One side has men on it and the other has women. This is an important point to consider given that this is a prominent example of the sauwastika, where we are given some context. This might also imply that the swastika and sauwastika have male or female connotations to them.

Fig.14: Melian amphora depicting Heracles and his bride. Source: John Boardman 1998.

Finally on this plate from Thasos, we see the hero Bellerophon during his fight with the Chimaera (fig.15). Among this scene, two swastikas can be found, one above Bellerophon himself, and the other underneath the Chimaera itself. The context of this plate, does not help incredibly when one attempts to decipher the symbolism of the swastika here. One could obviously point to the swastika beneath the Chimaera itself and make the assumption that it is there to represent the death of the Chimaera. But one when it comes to the swastika near Bellerophon himself, there are numerous theories one could come up with. Perhaps it is symbol of good here, thus implying that the other one is a symbol of evil. It might be that it is showing the luck or blessings that Bellerophon possesses at that moment. However it might also symbolise the fate of Bellerophon.

Fig.15: Cycladic plate depicting Bellerophon and Pegasus fighting the Chimaera. Found in the Archaeological Museum of Thasos. Author: Egisto Sani 2014.

Goddesses

The association of the swastika with deities is certainly seen during the Geometric and Orientalising periods. In the Geometric period, we certainly have evidence for the existence of the Olympian Pantheon, ranging from shrines to Zeus, Apollo, Demeter, Hera and Artemis (Coldstream 2003: 327-332). However in the Geometric period we find that the swastika can be found, especially, with images of Artemis. Given that Artemis was the goddess of the hunt, wild animals, wilderness, childbirth and virginity. She was also seen as a guardian of young girls and the bringer and alleviator of disease in women. Certainly all these attributes qualify as aspects of life. As we can see here this pot is decorated with various motifs including the swastika (fig.16).

Fig.16: Boeotian Late Geometric depiction of Artemis. Source: John Boardman 1998

We see birds and other animals but we also see a depiction of a female in the centre. Given the various wild animals we see, with the exception being the depiction of a bull, we could say with some certainty that this might be a depiction of Artemis (Boardman 1998: 48). The importance of this is that it gives the use of the Swastika some context. Here it not only gives us some grounding that the swastika is symbolic representation of life but it also gives us proof in the it being used in association with deities, this might also point to its use as an astronomical symbol as well. Likewise, this Orientalising piece (fig.17), where one can see the goddess with a hunting hound and three swastikas flanking them, I would say is in the same vein as the earlier ‘Geometric’ depiction of Artemis (Boardman 1998: 111), albeit with more of an emphasis on hunting.

Fig.17: Melian amphora featuring Artemis. Source John Boardman 1998.

Now Artemis is not the only goddess we see associated with the swastika, in this example we see it associated with, what one might presume, to be Demeter. In this image (fig.18) we see many swastikas being employed here, in association with the quatrefoil symbol, two birds, the remnants of what could a circle motif and especially in this case, females. While most of the females have sustained some damage, the one in the centre, can be seen in full view. This female is wearing a dress emblazoned with swastikas and she is holding her hands out over two swastikas, seen accompanied by the two birds flying above her, Here the majority of the swastikas are seen hovering over a series of diagonal/tangential lines stacked upon one and another. Before I address the symbolic significance of the Swastika, it is worth addressing what these ‘lines’ are supposed to represent. I have identified several possible meanings, the first being that these motifs are representative of vegetation in particular wheat. The way the lines protrude can immediately remind one of the way the wheat is often depicted. The second could be that they are nascent plants, possibly olive trees. The third is that they might be ‘heat lines’ possibly indicating that the land is in drought or to dry. The fourth is that they are actually supposed to be seen in conjunction with the swastikas that hover above them, and that they are the ‘magical rays’ emanating from them. Regardless of what they are specifically, it is clear that the swastika is symbolising some form of ‘life-giving’ quality. In the third interpretation, it might be that the Swastika is being used as a symbol of Demeter’s association with grains and the fertility of the earth, and her powers of regenerating land. It might be an assurance that despite the land being infertile at the moment, Demeter will regenerate the land.

Fig.18: Boeotion polos. Author of photo: Casper Jackson. Source of picture: John Boardman 1998.

Other

Boeotian bell idols are still quite an enigma, no scholars are very sure what the purpose of these figures are. This particular one is adorned with birds, various swastikas, circles and two motifs which might be wings or feathers or ferns (fig.19). Once again we see the motifs that are commonly seen in association with the swastika. We also can see an example of a ‘stacked’ or spiral swastika design, which in this case might be more of an astronomical or solar symbol, perhaps a crude representation of a star or the sun. I would maintain that we cannot be too sure of what the swastika is representative here regardless of the symbols associated with it.

Fig.19: Late Geometric Boeotian Bell-Idol. Source: John Boardman 1998.

On another one of these bell idols (fig.20), we see the swastika used, but in this case the typical motifs associated with the symbol, are absent. In the scene, decorated on the bell idol, we see various people, some possibly children given the height difference, all linked in a chain by arms, with rosette symbols above them. While it is unclear what exactly this scene is supposed to represent exactly, we can certainly see that there is a theme of life occurring here.

Fig.20: Late Geometric Boetian Bell-Idol. Author: Unknown

Later Examples

It would also benefit if one included an example from the Classical period to see whether any useful historical comparisons can be made. On this cup we see a depiction of Athena (fig.21), among other classical deities. Here the swastika does not so much feature as a standalone symbol but rather it is incorporated as part of the dress of Athena. Now the issue here is that what the swastika is meant to represent, in regard to depictions of deities is difficult at best. Athena, like many other gods and goddesses has more than one role, such as goddess of wisdom and warfare. Given that she was also the patron god of the city-state of Athens, it might be reasonable to assume that the swastika is still a representation of life, however in this case ‘civilized’ or ‘Athenian’ life. We see the swastika, in this example, become more focussed in its meaning, perhaps it is no longer this all-encompassing symbol of life but rather showing what the ideal life would be.

Fig.21: Classical cup from Tarquinia featuring Athena and other members of the Olympian Pantheon. Author: Donald Mackenzie 2014.

Conclusions

The swastika as we have seen, is a ‘complicated’ symbol. So many possible interpretations can be derived from it. We have seen it being used in association with deities, animals, mythology and people to name just a few. However all these are linked by one overarching trait, life. However this does not only mean that the swastika only emphasises and represents life in the sense of animals and plants, but rather living itself. We see it linked with hunting and cultivation, everyday characteristics of living in that period. The association with deities and the mythological, elements that were ingrained heavily into Greek life. It could be reasonably interpreted as a good luck charm to try and help a man or woman in their passages through life. While its use during the Archaic period is very well documented and very pronounced, the use of it in the Classical period is quite limited, its use is never as prominent as it was in previous years. This decline leads us to question, why was it that this all- encompassing symbol withered in use? Was it the growth of the narrative art? Was it the development of a Greek Identity or the desire to be more unique? Was it the fear of the Persians, the Orientals or foreigners in general?3 These are certainly questions that one has to consider when analysing such an enigma as the swastika.

Author: Casper Jackson Casper Jackson

Cardiff University, Ancient History, Graduate Student

Reference List:

Boardman J. 1998 Early Greek Vase Painting London: Thames & Hudson pg. 48, 111 Coldstream J.N 2003 Geometric Greece London: Routledge pg. 327-332

Dumoutier G. L 1885 Revue d’ Ethnographie, Paris, IV, 1885, pp. 327-329.

Garber M. 2003 The Medusa Reader London: Psychology Press pg. 2

Goblet D’Alviella E. 1894 The Migration of Symbols. London: A. Constable and Co. pg. 39, 60

Greg R.P 1885 The Fylfot and Swastika , Archæologia, XLVIII, part 2 pg. 298

Roes A. 1933 Greek Geometric Art: Its Symbolism and its Origin Haarlem: H.D. Tjeenk Willink & Zoon N.V. pg. 13-17

Schliemann H. 1881 Ilios: The City and Country of the Trojans New York: Harper and Brothers pg. 346, 350

Snodgrass A. 1980 Archaic Greece: The Age of Experiment Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press pg. 13

Waring G. 1874 Ceramic Art in Remote Ages London: John B. Day pg. 10

3 This might be plausible if one chooses to consider the Swastika being of Oriental or Eastern Origin and the theory that the swastika has a near universal meaning among all cultures.

Wilson T. 1894 The Swastika: The Earliest Known Symbols and its Migrations: With Observations on the Migration of Certain Industries in Prehistroic Times in the Report of the

U.S National Museum for 1894. pg. 769, 771-772

Internet References:

www1: http://www.pantheon.org/articles/s/sphinx.html

www2: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3Dsfi%2Fggw

Illustration references:

Cover Photo: Detail Of A Greek Vase In The British Museum Ram, meander Swastika circles, dots, and crosses in Salzmann, “Necropole de Camire,” LI, and Goodyear,“Grammar of the Lotus,” pl. 28, fig. 7 found in Wilson T. 1894 The Swastika:

Fig.1: Late Geometric 1b pitcher. Found in Attica. Source: British Museum.

Fig.2: Milesian (MWG) Oinochoe. Author: Katie R 2014.

Fig.3: Fig. 3 Late Geometric Pyxis. Museum of Ancient Agora of Athens. Author: Heidi Kontkanen 2012.

Fig.4: Late Geometric Ischian Krater. Source: John Boardman 1998.

Fig.5: Proto-Attic Amphora. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Author: Ad Meskens 2009. Fig.6: Late Wild Goat style plate from Rhodes. Source: John Boardman 1998.

Fig.7: Samian Wild Goat Krater Panel. Sourcer: John Boardman 1998.

Fig.8: Milesian Wild Goat Oinochoe. Source: Louvre Museum. Found in Dimitris Paleothodoros 2007, "Wild Goat Style Pottery".

Fig.9: Gorgon/Gorgon-Headed Goddess plate from Rhodes. British Museum. Author: Marie- Lan Nguyen 2007.

Fig.10: Late Wild Goat Style, possibly Rhodian, plate from Tocra featuring a Sphinx design. Source: John Boardman 1998.

Fig.11: Hirschfeld Krater. Scene depicting ekphora and a chariot race. Funeral of Patroclus? Source: John Boardman 1998.

Fig.12: Rhodian Middle Wild Goat style plate depicting Menelaus and Hector fighting over the body of Euphorbus. Author: Jastrow 2006.

Fig.13: Proto-Attic Amphora depicting the blinding of Polyphemus by Odysseus and his soldiers. Found in Archaelogical Museum of Eleusis. Author: Napoleon Vier 2003.

Fig.14: Melian amphora depicting Heracles and his bride. Source: John Boardman 1998.

Fig.15: Cycladic plate depicting Bellerophon and Pegasus fighting the Chimaera. Found in the Archaeological Museum of Thasos. Author: Egisto Sani 2014.

Fig.16: Boeotian Late Geometric depiction of Artemis. Source: John Boardman 1998. Fig.17: Melian amphora featuring Artemis. Source John Boardman 1998.

Fig.18: Boeotion polos. Author of photo: Casper Jackson. Source of picture: John Boardman 1998.

Fig.19: Late Geometric Boeotian Bell-Idol. Source: John Boardman 1998. Fig.20: Late Geometric Boetian Bell-Idol. Author: Unknown

Fig.21: Classical cup from Tarquinia featuring Athena and other members of the Olympian Pantheon. Author: Donald Mackenzie 2014.